No products

OLIVER TWIST

Foreword

by Simon Callow

Simon Callow is an English actor, writer and director who has also written extensively about Charles Dickens. His most recent publication is his 2012 biography of Dickens, Charles Dickens and the Great Theatre of the World.

To read the manuscript of Oliver Twist is to be plunged headlong into the almost inconceivable waves of energy which swept the young Dickens along as he embarked on what was to become his second novel. It was 1837, he was twenty-five years old, and had been writing professionally only since 1834. He had started by contributing comic stories to the Monthly Magazine, and then—under a pseudonym, Boz, borrowed from his younger brother Moses—shyly penned a series of Street Sketches of London life for the Morning and Evening Chronicles, where he worked as a reporter. The stories proved hugely popular, and before long were collected together and issued in book form, with vivid illustrations by the political cartoonist George Cruikshank, under the title Sketches by Boz; one of them, A Bloomsbury Christening, had even before publication been successfully adapted for the stage by the popular comedian and dramatist J. B. Buckstone. The success of the Boz sketches encouraged the recently established publishers Chapman and Hall to commission Dickens to write what became The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, a venture somewhat haphazardly entered into as a serial, in weekly instalments, without any real plot or overall plan. It was only moderately successful at first, but the moment Sam Weller, Pickwick’s droll cockney servant, made his appearance, it became a sensation, each fresh instalment eagerly anticipated by its readers, who ranged from street sweepers to privy councillors, its exuberant and largely affectionate satire a distorting mirror of society in which Britons were amused to recognise themselves. More or less overnight, Dickens became the humourist laureate of the British people.

His publishers, Messrs Chapman and Hall, quickly discovered that their new author had very firm views about the way he wanted his work to be presented; indeed, the whole venture, which had started with their proposal that he should provide amusing texts to accompany Robert Seymour’s drawings of the antics of some cockney would-be huntsmen, turned, on Dickens’s insistence, into an entirely different story about the ineffable Samuel Pickwick and his band of amateur scholars, in their leisurely quest to investigate the life of nature; Seymour was invited to contribute illustrations. The frustration and humiliation of this proved too much for the wretched man, who, in the middle of working on Chapter Three, blew his brains out.

After the briefest of pauses, Dickens and his publishers resumed, recruiting the popular illustrator Hablôt Knight Browne to replace poor Seymour. Browne (or “Phiz”, as he styled himself) supplied the riotously vivid illustrations for Chapter Four, the chapter in which Sam Weller appears for the first time, and thereafter more than kept pace with Dickens, as the young author—a complete novice at fiction, one has to remind oneself—turned out an inexhaustible supply of ever riper characters, in ever more absurd situations, many of them familiar types and well-worn plotting devices from the contemporary theatre of which he was such an insatiable fan. His readers, across the English-speaking world, and increasingly in other languages, adored the book and its author; it was even, within a year, translated into Russian.

Dickens was briefly taken aback by his new fame, but seized it with both hands. People encountering the young new celebrity were astonished by him. His fellow journalist John Forster, smitten on sight, wrote of his “quickness, keenness, practical power, the eager, restless, energetic outlook on each several feature, that seemed to tell so little of a student or writer of books and so much of a man of action and business in the world. Light and motion flashed from every part of it.” The less-easily impressed sage Thomas Carlyle wrote to his wife Jane “He is a fine little fellow—Boz, I think,” noting the “clear, blue, intelligent eyes that he arches amazingly, large, protrusive, rather loose mouth, a face of the most extreme mobility, which he shuttles about—eyebrows, eyes, mouth and all—in a very singular manner while speaking.” “What a face to meet in a drawing room!” cried the essayist and poet Leigh Hunt. “It has the life and soul in it of fifty human beings!”

The possessor of these singular characteristics immediately turned his newfound celebrity to good use by making speeches, all of them with an underlying theme, striking blows on behalf of the oppressed— the working classes, for the most part, but also, in his first great speech, authors, ruthlessly exploited by publishers who then had the right to buy the copyright in books outright. He had already severed relations with John Macrone, the publisher of the Boz Sketches; before long, he would fall out with Chapman and Hall. But there was no avoiding publishers: he depended on them, and while he continued writing Pickwick, he entered on the crest of the wave of his ever-increasing success into a number of new contracts. In August 1836, having made the deadline for instalment No 7 of Pickwick by the skin of his teeth, he signed a contract with Thomas Tegg to write a children’s book to be called Solomon Bell the Raree Salesman (the book was never written), and then another one with the printer and publisher Richard Bentley to write two three-volume novels (although he had only recently promised one to Macrone). He wrote more Boz Sketches for the Morning Chronicle, gave in to his passion for the stage by writing a musical play, The Strange Gentleman, adapted from one of the sketches already in print, and began work on an original libretto for a rustic operetta, The Village Coquettes. In addition, he was planning a three-volume novel he called Gabriel Vardon, the Locksmith of London (which would eventually, after much procrastination and re- writing, become Barnaby Rudge). Finally, his wife gave birth (painfully) to their first child, Charley. All of this happened within a few months, while he continued to produce the riotously funny monthly instalments of Pickwick. Unsurprisingly, he reported to a friend that he was “really half dead with fatigue.”

In the midst of all this activity, he was invited by Richard Bentley to become first editor of his new magazine, modestly entitled Bentley’s Miscellany, a task which Dickens took on with brio and fanatical attention to detail: a Dickens half dead with fatigue still had the energy of ten men. The magazine was 104 pages long, which took a great deal of commissioning, a considerable quantity of cutting and rewriting, as well as a sizeable amount of new writing from him personally. His very first contribution, on 1 January 1838, in the first edition of the Miscellany, was a diverting and grotesquely exuberant account of provincial delusions which he called The Public Life of Nicholas Tulrumble, Mayor of Mudfog:

Mudfog is a healthy place—very healthy;—damp, perhaps, but none the worse for that. It’s quite a mistake to suppose that damp is unwholesome: plants thrive best in damp situations, and why shouldn’t men? The inhabitants of Mudfog are unanimous in asserting that there exists not a finer race of people on the face of the earth; here we have an indisputable and veracious contradiction of the vulgar error at once. So, admitting Mudfog to be damp, we distinctly state that it is salubrious.

As he wrote, something seems to have stirred deep in his subconscious, provoking him to send a letter to Bentley telling him that he had hit on “a capital notion” for himself, which would “bring out Cruikshank”, the brilliant illustrator of the Boz Sketches; indeed, there is some evidence that Cruikshank and Dickens developed the initial idea together. Dickens rapidly produced the first instalment of this story, which he called Oliver Twist or, the Parish Boy’s Progress; in it, as first published in the Miscellany, it is revealed that Oliver is born in Mudfog, and it may be that Dickens originally saw the new story as part of the saga of that town. But as he had with Pickwick, he plunged headlong into writing with little or no forward planning, simply imagining his characters and letting them rip; soon enough he realised that they had nothing to do with Mudfog, and that he had bigger fish to fry than mere provincial satire; in the first bound (1841) edition of the book, he duly removed any reference to the place. What really exercised him, he realised, was the nefarious New Poor Law of 1834 and its catastrophic consequences, especially for the young. Accordingly, with some boldness, he took a boy as his hero, the first author in English literature ever to do so.

“I wished to shew, in little Oliver,” he said in the Preface he wrote to the 1841 edition of the book, “the principle of Good surviving through every adverse circumstance, and surviving at last.” He was determined not to glamourise the criminals among whom Oliver falls. Rejecting the romantic view propagated by John Gay in his Beggars’ Opera, Dickens instead took the savagely realistic engravings of Hogarth as his model. “IT IS TRUE,” he wrote—his capitals—in the Preface, “Here are no canterings on moonlit heaths, no merry-makings in the snuggest of all possible caverns.” The urban underbelly was his subject: “the cold, wet, shelterless midnight streets of London; the foul and frowzy dens, where vice is closely packed and lacks the room to turn; the haunts of hunger and disease, the shabby rags that scarcely hold together.” He was describing “the very scum and refuse of the land,” which he knew at first hand, from his almost nightly walks across the city. “I have, for years, tracked it through many profligate and noisome ways, and found it still to be the same.” He listed his characters in unvarnished form: Sikes, he writes, “is a thief, and Fagin a receiver of stolen goods; the boys are pickpockets, and the girl is a prostitute.” The very use of the last word stopped Dickens’s readers dead in their tracks—no wonder Lord Melbourne tried to dissuade the young Queen Victoria (who ascended the throne the year the book started to appear) from reading a book about “Workhouses and coffinmakers and pickpockets… I don’t like that low debasing style.” Dickens was determined to force the Lord Melbournes of this world to look at things as they were. “It occurred to me that to do this, would be to attempt something which was greatly needed, and which would be a service to society. And therefore I did it as I best could.” To his natural exuberance, sharp eye and sheer joy in storytelling was added a new passion for reforming society’s ills, which of course only drove him harder.

He devoted two weeks a month to Oliver and two to Pickwick. That he could in his head simultaneously juggle their two hugely different worlds almost defies belief. But he was juggling more just the two novels: there was all the other writing he was doing on the side. He seems never, in these early days, to have been able to resist a commission, constantly mindful of the expense of maintaining a family, which, like the novels, also appeared in regular instalments. Added to all this were the burdens of editorship, with a proprietor whose constant interference and sly commercial ways he found increasingly irksome. He also maintained a personal correspondence which even then was voluminous. He was under huge and constant pressure, but, except with Bentley—“the Burlington St brigand”, as he called him—his essential good humour rarely faltered.

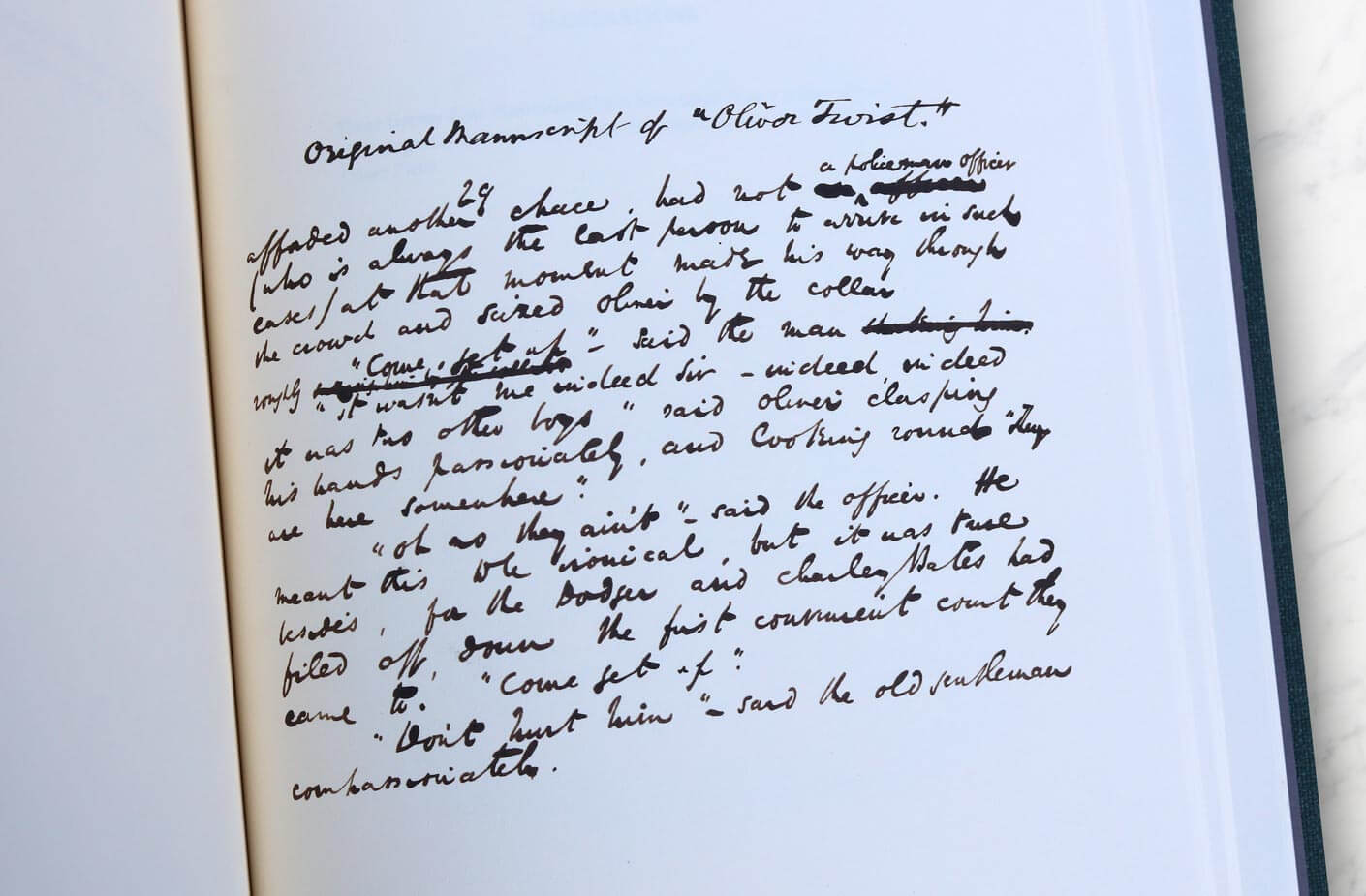

He was just twenty-six years old, but his unstoppable joie de vivre is nonetheless astonishing. After a hard morning of writing and editing, he needed the relief of physical exercise, walking, or, even better, riding, ideally all over Hampstead Heath with his new best friend John Forster, followed by a good supper and a few flagons of wine at Jack Straw’s Castle. Forster would receive his summonses out of the blue: “Is it possible,” the rapidly scribbled note would say, “that you can’t, oughtn’t, shouldn’t, mustn’t, won’t, be tempted, this gorgeous day!” How could Forster refuse? How could anyone? “I start precisely—precisely, mind—at half-past one. Come, come, come, and walk in the green lanes. You will work the better for it all week. COME! I shall expect you.” Or “Where shall it be? Oh where?—Hampstead? Greenwich? Windsor? WHERE?????? While the day is bright, not when it has dwindled away to nothing! For who can be of any use whatsomdever such a day as this, excepting out of doors?” Or it might just be: “A hard trot of three hours?” and then, without waiting for a reply: “So engage the osses.” The manuscript so handsomely reproduced here testifies to the passion and urgency of his writing, as do the later corrections and alterations to the text. The editors of the great Pilgrim Edition of the Collected Letters observe a change in his writing comes about at just this time: “the pothooks used for forming capital M or N that he would have learned at school,” according to Michael Slater, “now yielded to a more dashing way of writing them.” His confidence was growing day by day, as the two books, so different, poured forth to ever greater acclaim.

In the midst of all this wild hyperactivity, he was dealt a terrible blow: his sister-in-law, seventeen-year-old Mary Hogarth, who was living with the young couple and their small children, and for whom Dickens had a deep tendresse, suddenly died in their handsome new house in Doughty Street, in North London. They were both devastated. Dickens’s wife, Catherine, Mary’s sister, had a miscarriage, and Dickens himself was so affected by the double tragedy that he stopped writing. The loss of the exquisite (and in Dickens’s view flawless) young woman haunted him, and his fiction, for the rest of his life. On a less elevated plane, he was also increasingly exasperated with his publisher, who he felt was exploiting him. First of all, Dickens was paid less when he failed to write exactly the designated number of words for each instalment. Sharply aware of the change in his situation since the original contract with Bentley had been signed, he asked that Oliver Twist be allowed to stand as one of the novels he had agreed to write for him. Bentley refused, so again Dickens stopped writing Oliver, submitting two more stories about Mudfog in place of the regular instalments. Bentley caved in. But Dickens had used the month in which he stopped writing Oliver Twist to think hard about his approach to writing, having been incensed by a recent essay in The Quarterly Review which, while admiring Dickens’s inventiveness and wit, doubted his ability to sustain a purposeful narrative. “He has risen like a rocket,” said the author, Abraham Hayward, “and he will come down like the stick.”

Dickens was determined to defy “Mr Hayward and all his works” and began thinking very hard about how to continue with the book. In doing so, he saw clearly that there was only so much more mileage he could get out of his boy hero, but that Nancy, who had grown into a much richer figure than the mere gangster’s moll she had first appeared to be, offered remarkable possibilities, especially in contrast to the figure of Rose Maylie, whom Dickens inevitably patterned after his flawless sister-in-law, Mary. Nancy would be the new, tragic heroine of the work, and the working out of her destiny in its pages would transform a mere serial into a genuine novel. And indeed, when he resumed, he wrote with new vigour and focus and a much tighter grip on the book, building towards the terrible and inevitable climax in which Bill Sikes kills Nancy. As well as effecting this major gear change—turning the ship around, in effect—he was already, with typical multiplicity of projects, pondering a new serial for Chapman and Hall which would focus on the abuse of schoolchildren; The Pickwick Papers was done, and Nicholas Nickleby was germinating within him. But that was by no means all: in addition to continuing as editor of the Miscellany, he agreed out of affectionate regard for the great clown Joey Grimaldi, recently deceased, whom he had seen as a boy and never forgotten, to take on the substantial task of re-working the old man’s Memoirs. He also tossed off, almost without thinking about it, an attractive little collection called Sketches of Young Gentlemen for Chapman and Hall. “He never wrote,” said Forster, “without the printer at his heels”. Around this time, he tried to take out life insurance and failed, because, he said, bemused, “they seem to think I work too hard.”

The last instalment of Oliver Twist was published in Bentley’s Miscellany in April 1839, while the bound edition appeared, volume by volume, from 1838 to 1841. As soon as he finished writing, in October of 1838, he started revising the text, partly to iron out inconsistencies in the plot resulting from his changed conception of Nancy and her destiny, and partly to render her less coarse and violent. Often, the changes were made to simplify the style, “leaving more to the imagination,” as Katharine Tillotson says in her famous 1966 edition of the novel. “Descriptive epithets and phrases are constantly deleted, rarely added.” There were further changes to the same effect in 1841 and again in 1846.

Oliver Twist remains among the best loved and indeed most read of Dickens’s novels; but there is another fascination to it. Quite apart from its passion and its power, the indelible descriptions of a brutal underworld, the heart-stopping progress of an innocent through a corrupt world, its depiction of a vanished London, and the characters which have passed into the collective unconscious, it shows us the young genius in the very act of mastering his craft—a uniquely exuberant, inventive, observant, compassionate tyro turning himself, by sheer willpower, into one of the greatest writers in the English—or any other—language. It is thrilling to be able to watch it happen as he, the great literary conjuror, might have said himself, before one’s very eyes.

© SP Books / Simon Callow, 2020