Lady Susan by Jane Austen

Sky blue edition,

numbered from 1 to 1,000

Lady Susan, Jane Austen’s manuscript

Lady Susan : the only complete surviving manuscript of Jane Austen’s fiction, reproduced in a graphically restored version for the first time.

Aged 18 or 19, when most young women of the Georgian period would have been thinking about engagement and marriage, Jane Austen was preoccupied with getting the fruits of her already fertile imagination down on paper. Though encouraged by family to pursue her literary interests, she could not have anticipated her eventual fame as one of the world’s most beloved authors, whose works would be widely adapted for film and theatre.

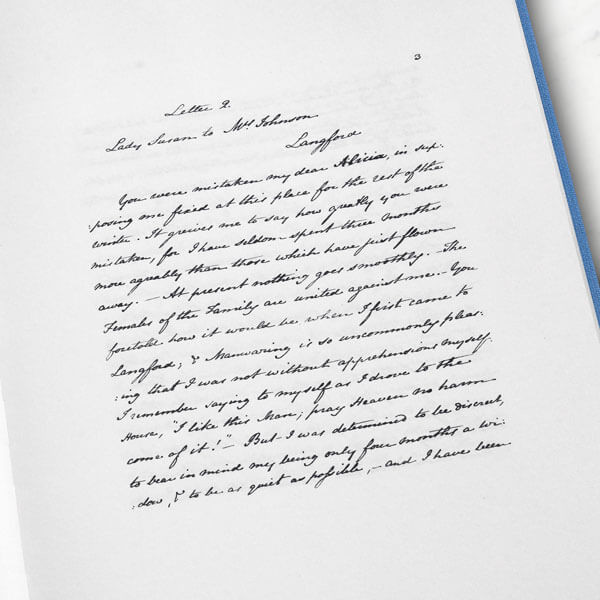

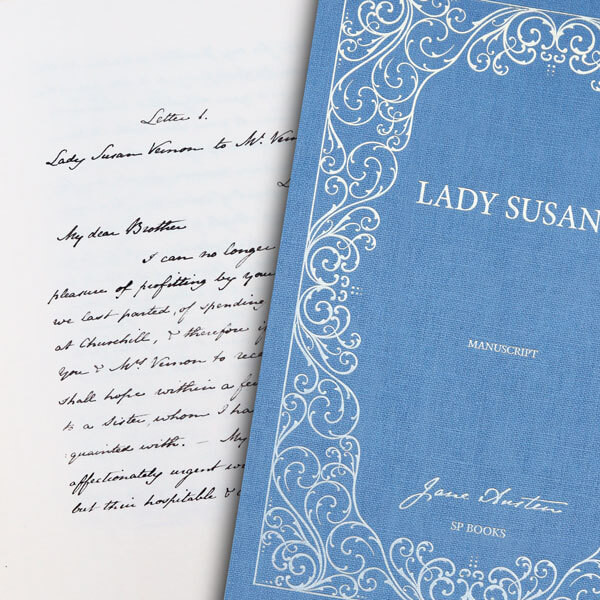

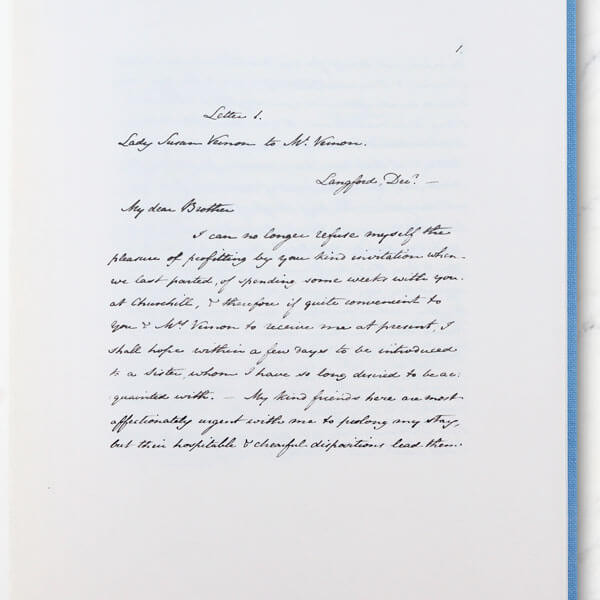

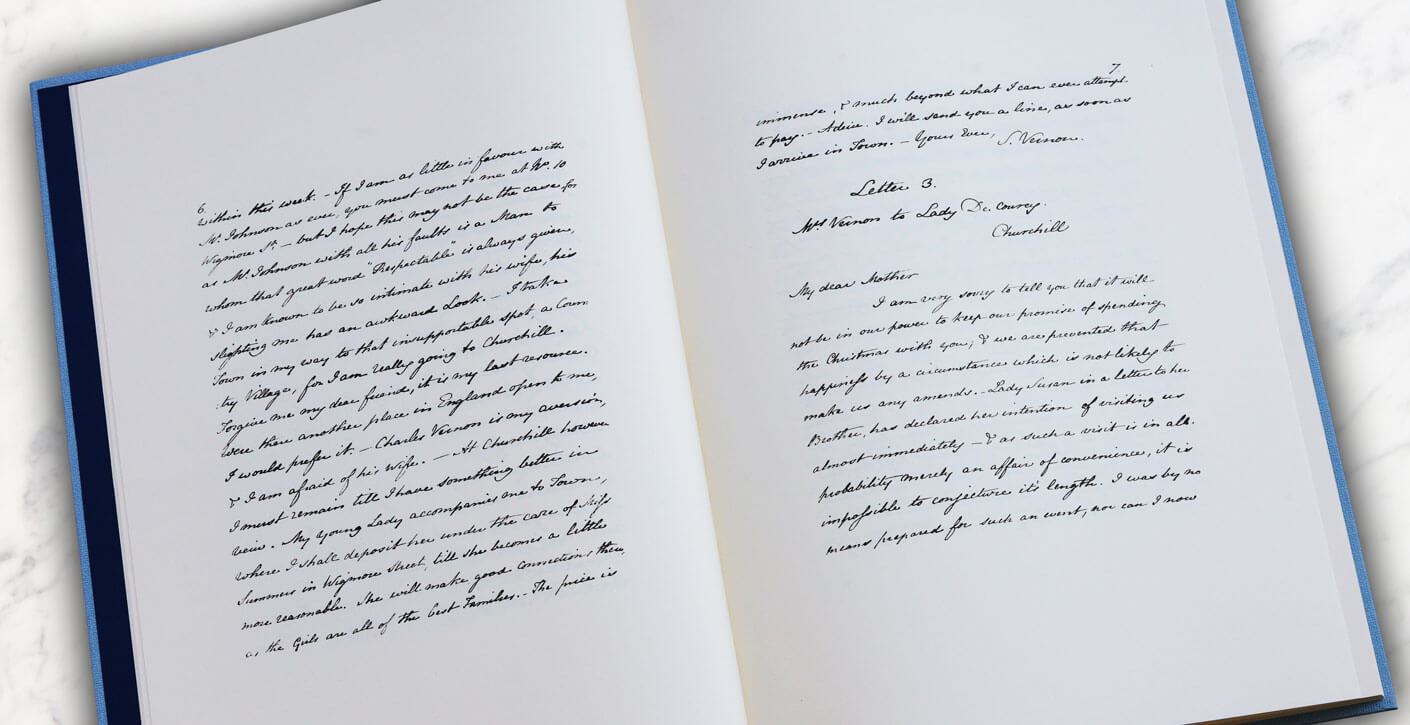

The precocious Jane most likely started writing Lady Susan in the early 1790s while staying at Steventon rectory, her childhood home in Hampshire. She wrote out this fair copy in Bath no earlier than 1805—the date of watermarks found on the paper stock used for this manuscript. Written and paginated in her hand, this 158-page manuscript is dedicated to Lady Knatchbull, Austen’s niece and considered by her as a ‘sister’.

The novel first appeared posthumously in 1871, when Lady Knatchbull authorised the writer’s nephew, James Edward Austen-Leigh, to publish it in the second edition of his Memoir of Jane Austen. This Lady Susan was printed from a non-authorial copy, as the manuscript only emerged after Lady Knatchbull’s death in 1882. First inherited by her son, it passed through the hands of several buyers until the mid-20th century. When sold at the Rosebery sale in 1933, it was described as “THE FINEST LITERARY MS. OF JANE AUSTEN extant”. In 1947, it was purchased for $6750 by Belle da Costa Green, Director of the Morgan Library in New York, where the manuscript is now housed.

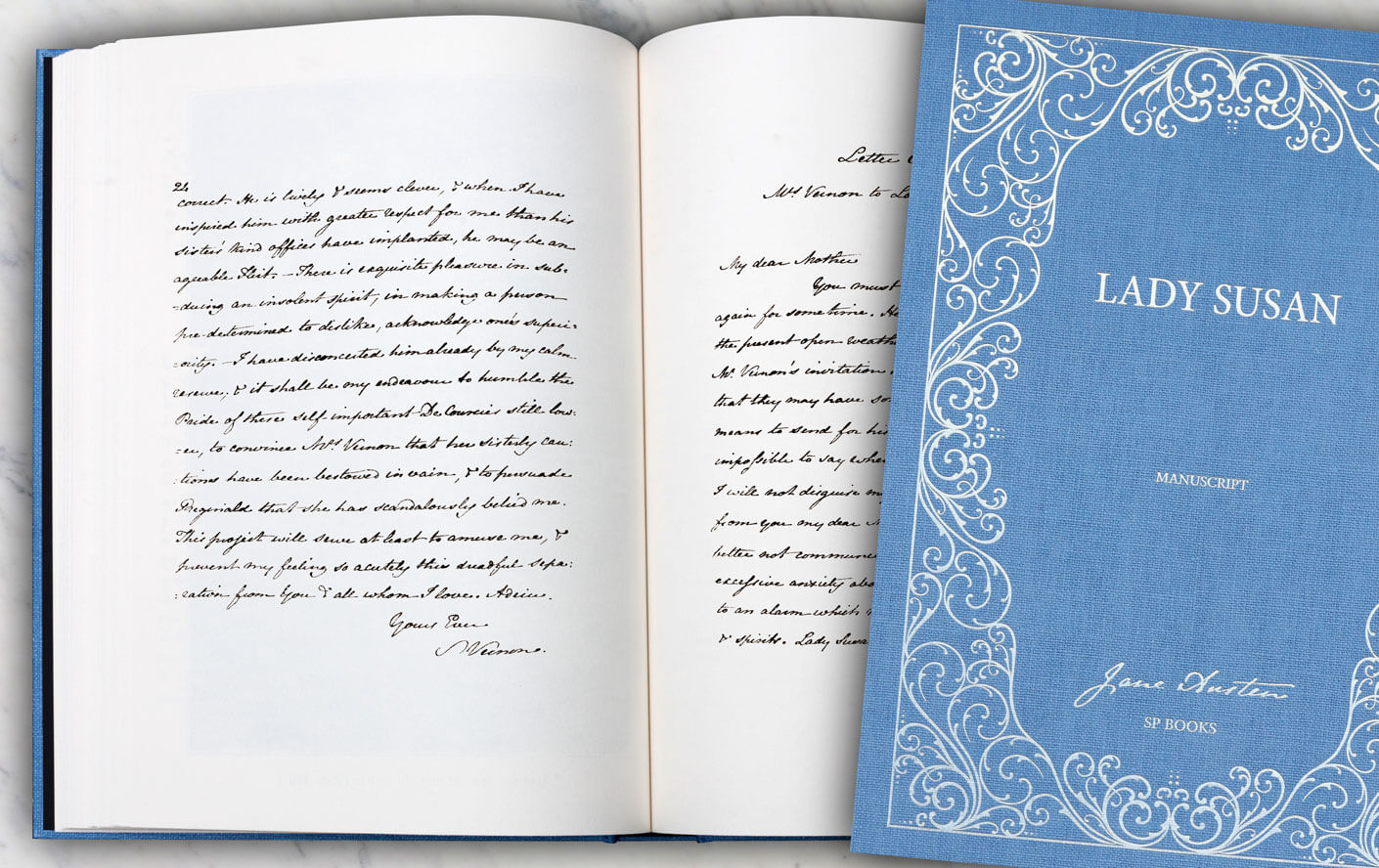

This edition was produced in collaboration with the prestigious Morgan Library & Museum of New York, allowing readers to discover the pages once handwritten by Jane Austen in a graphically-restored version of the original.

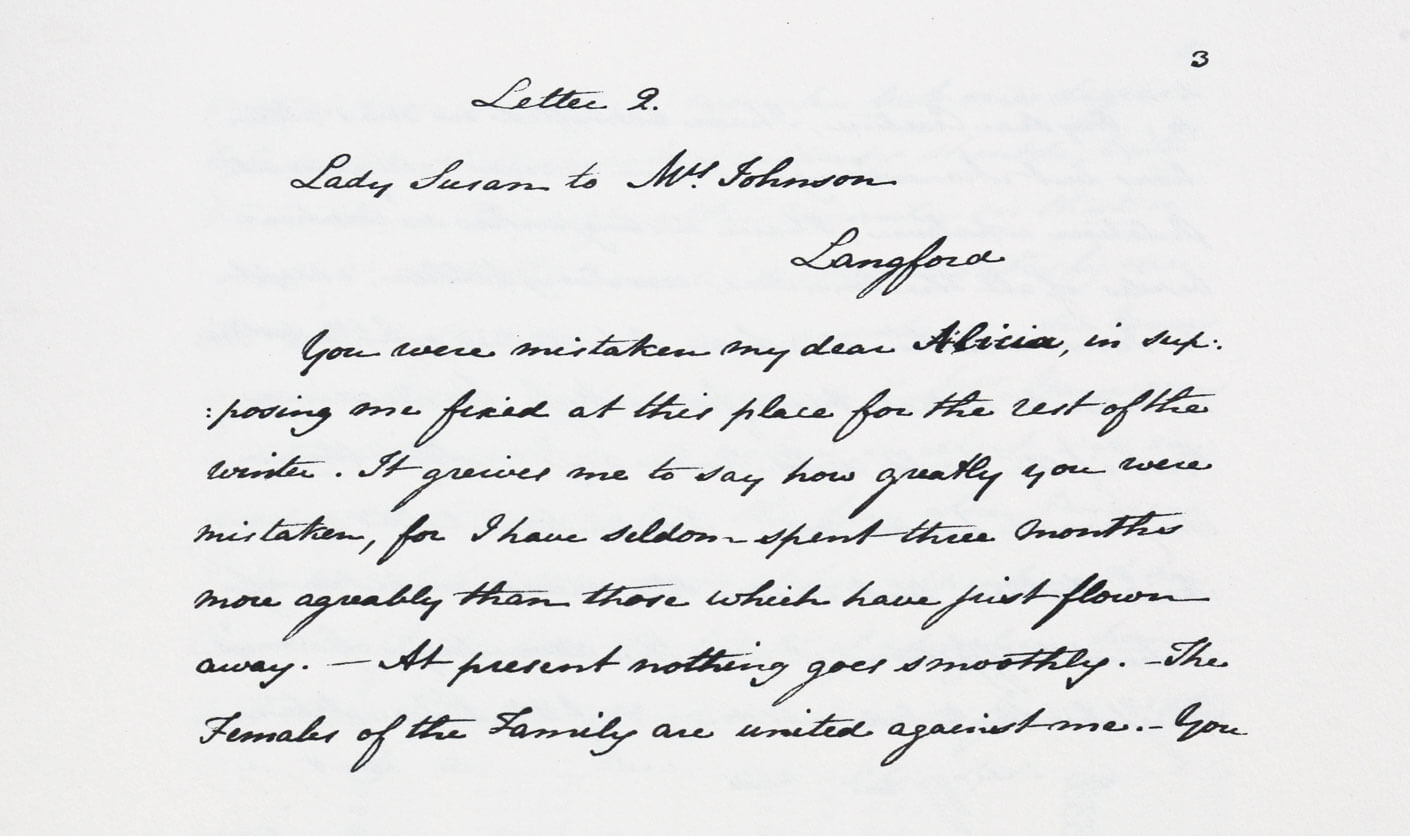

Lady Susan, an epistolary novel

Probably influenced by fashionable epistolary novels by Samuel Richardson and Dangerous Liaisons (Les Liaisons dangereuses) by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos, Austen’s scathing novella tells the story of a seductive widow whose morals leave much to be desired. The character of Lady Susan was probably inspired by la Marquise de Merteuil, as Jane Austen’s cousin, Eliza de Feuillide, lived in France between 1779 and 1790.

When the novel was first published, it was officially titled with the name of its main character though the manuscript itself remains untitled. However, it might have already been known under this title within Austen's family.

The manuscript contains such memorable quotes as:

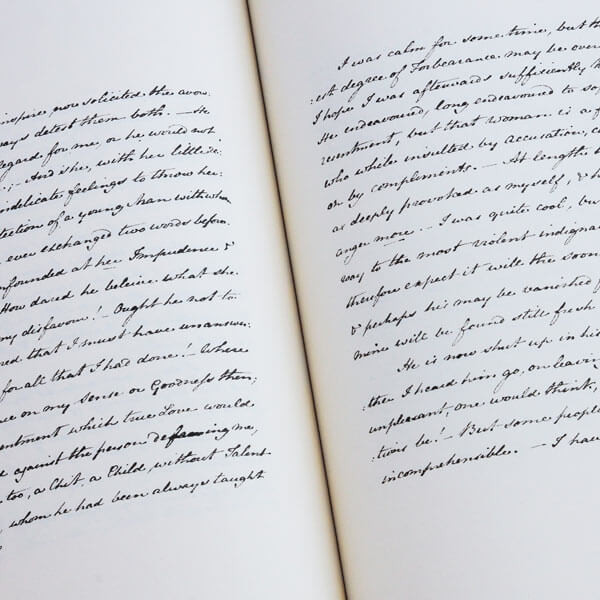

‘There is exquisite pleasure in subduing an insolent spirit, in making a person predetermined to dislike acknowledge one's superiority’ (Letter 7)

...epitomising the ambience of seduction and manipulation which is deployed throughout the 41 letters composing the novel.

Lady Susan remains Jane Austen’s only epistolary novel. She drafted four epistolary novels in the 1790’s, including Lady Susan and a first draft of what would become her first published novel, Sense and Sensibility. However, except for Lady Susan, she rewrote all three of them into narratives – each one including letters, but rejecting the pure epistolary structure she had begun with (see Susan Pepper Robins’ work). Thereafter, Austen didn’t pursue the epistolary form, but nevertheless, according to Austen specialists Christine Alexander and David Owen, the “particular use she makes of the letter form in Lady Susan” might even have “heightened her understanding of the letter’s value as a vital narrative element in her maturing fiction”.

A manuscript to be treasured

This 158-page document remains Jane Austen’s only complete manuscript novel, the other surviving drafts being those of her unfinished works, The Watsons and Sanditon. There are no complete manuscripts for her two best-known novels, Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice – or, at least, they have never come to light. According to Austen scholar Kathryn Sutherland, these drafts were probably “routinely destroyed” after they were published in book form. This, as well as the care she took with Lady Susan’s fair copy, establishes this manuscript as “a literary object to be treasured”.

Jane Austen, a self-assured and modern novelist

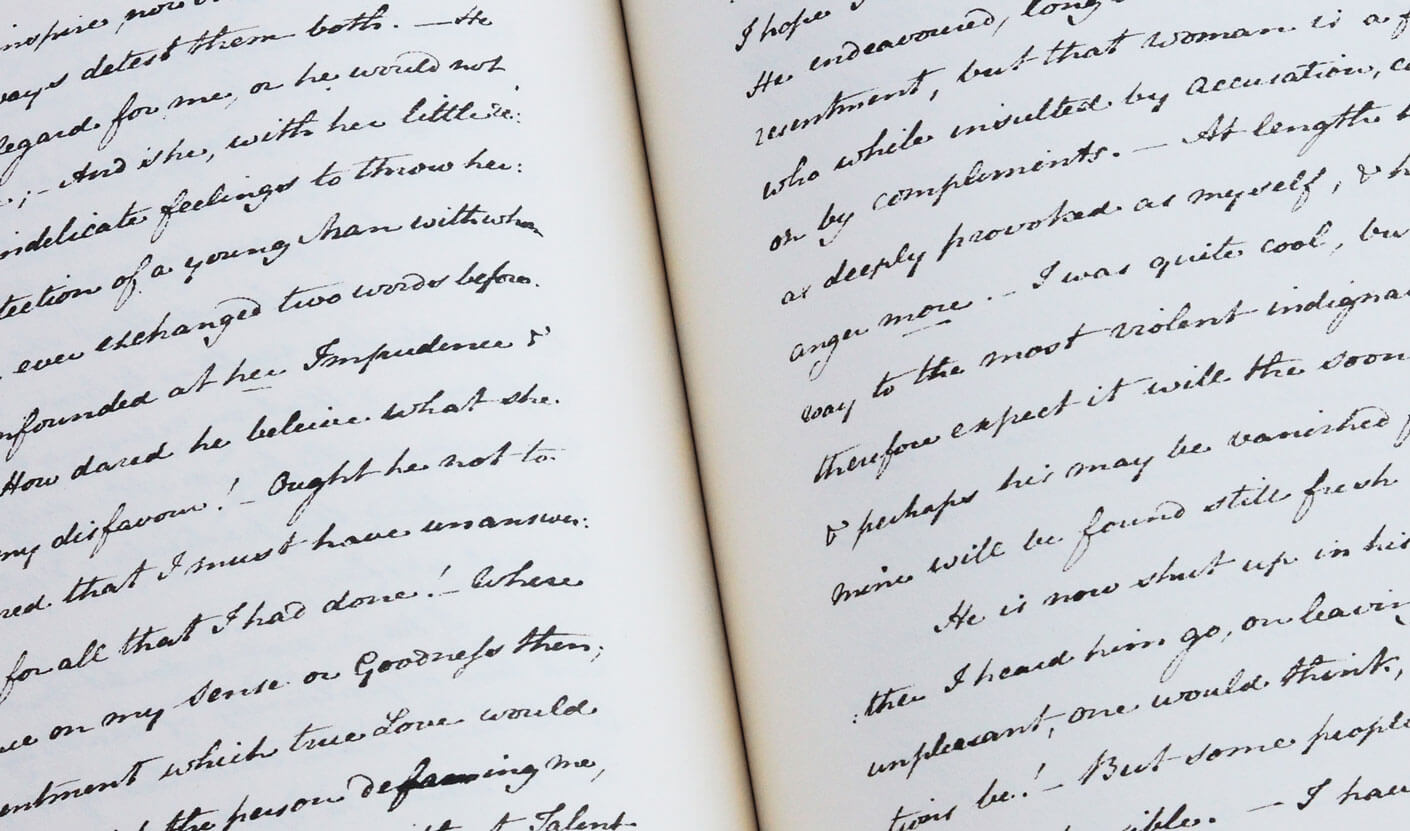

As a document it reveals much about Jane’s early self-assurance as a novelist, her fluency of thought and her unexpectedly modern use of punctuation—much favouring the use of dashes. Though it was later rebound into a different format, the manuscript originally took the form of a bound quarto notebook, which, according to Kathryn Sutherland, was “made in the same manner as those used for the three volumes of [Austen’s] teenage writings”. The way she wrote the manuscript, from top to bottom of the page leaving almost no margins and very little interlinear space, suggests she was trying to economise her paper usage. There are very few corrections in the manuscript of Lady Susan but when she does indeed make edits, she cautiously “squeezes in the corrections in the very small interlinear space”.

Posterity

Pride and Prejudice, Sense and Sensibility, Emma, Northanger Abbey… which other writer, especially a woman of the Georgian era, can boast about having made such an impression, in just a few years of writing, upon her era, the history of literature, and generations of readers?

Jane Austen became a published writer with Sense and Sensibility in 1811, a work which was soon followed by Pride and Prejudice in 1813, Mansfield Park in 1814 and Emma in 1816. The four novels met great success during her lifetime but the anonymity maintained by her publisher prevented her from achieving fame. However, her novels were read as far as the court of the future king George IV and praised by Sir Walter Scott. Her two other well-known novels, Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, were published after her death at the age of 41, in 1817.

In 1870, the publication of A Memoir of Jane Austen written by her nephew James Edward Austen-Leigh reassessed her life and works. In 1833, the publication of the complete set of her novels in six volumes by Richard Bentley contributed to her posthumous success, and since that time the writer inspired countless essays, works and adaptations in multiple forms. Today, Austen’s eager readers can visit The Jane Austen Centre, which is located on the same street the writer last lived in Bath, where she wrote this manuscript.

Lady Susan was adapted into a film in 2016 by American director Whit Whitney Stillman (Metropolitan). Entitled Love and Friendship, it is an acerbic romantic comedy in which Lady Susan is played by British actress Kate Beckinsale.

Deluxe edition

Numbered from 1 to 1,000, this Sky blue edition is presented in a large format handmade slipcase.

Printed with vegetable-based ink on eco-friendly paper, each book is bound and sewn using only the finest materials.

Mrs Dalloway: Thanks to a new reproduction of the only full draft of Mrs. Dalloway, handwritten in three notebooks and initially titled “The Hours,” we now know that the story she completed — about a day in the life of a London housewife planning a dinner party — was a far cry from the one she’d set out to write (...)

The Grapes of Wrath: The handwritten manuscript of John Steinbeck’s masterpiece The Grapes of Wrath, complete with the swearwords excised from the published novel and revealing the urgency with which the author wrote, is to be published for the first time. There are scarcely any crossings-out or rewrites in the manuscript, although the original shows how publisher Viking Press edited out Steinbeck’s dozen uses of the word “fuck”, in an attempt to make the novel less controversial. (...)

Jane Eyre: This is a book for passionate people who are willing to discover Jane Eyre and Charlotte Brontë's work in a new way. Brontë's prose is clear, with only occasional modifications. She sometimes strikes out words, proposes others, circles a sentence she doesn't like and replaces it with another carefully crafted option. (...)

The Jungle Book: Some 173 sheets bearing Kipling’s elegant handwriting, and about a dozen drawings in black ink, offer insights into his creative process. The drawings were not published because they are unfinished, essentially works in progress. (...)

The Lost World: SP Books has published a new edition of The Lost World, Conan Doyle’s 1912 landmark adventure story. It reproduces Conan Doyle’s original manuscript for the first time, and includes a foreword by Jon Lellenberg: "It was very exciting to see, page by page, the creation of Conan Doyle’s story. To see the mind of the man as he wrote it". Among Conan Doyle’s archive, Lellenberg made an extraordinary discovery – a stash of photographs of the writer and his friends dressed as characters from the novel, with Conan Doyle taking the part of its combustible hero, Professor Challenger. (...)

Frankenstein: There is understandably a burst of activity surrounding the book’s 200th anniversary. The original, 1818 edition has been reissued, as paperback by Penguin Classics. There’s a beautifully illustrated hardcover, “The New Annotated Frankenstein” (Liveright) and a spectacular limited edition luxury facsimile by SP Books of the original manuscript in Shelley's own handwriting based on her notebooks. (...)

The Great Gatsby: But what if you require a big sumptuous volume to place under the tree? You won’t find anything more breathtaking than SP Books ’s facsimile of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s handwritten manuscript of The Great Gatsby, showing the deletions, emendations and reworked passages that eventually produced an American masterpiece (...)

Oliver Twist: In the first ever facsimile edition of the manuscript SP Books celebrates this iconic tale, revealing largely unseen edits that shed new light on the narrative of the story and on Dickens’s personality. Heavy lines blocking out text are intermixed with painterly arabesque annotations, while some characters' names are changed, including Oliver’s aunt Rose who was originally called Emily. The manuscript also provides insight into how Dickens censored his text, evident in the repeated attempts to curb his tendency towards over-emphasis and the use of violent language, particularly in moderating Bill Sikes’s brutality to Nancy. (...)

Peter Pan: It is the manuscript of the latter, one of the jewels of the Berg Collection in the New York Public Library, which is reproduced here for the first time. Peter’s adventures in Neverland, described in Barrie’s small neat handwriting, are brought to life by the evocative color plates with which the artist Gwynedd Hudson decorated one of the last editions to be published in Barrie’s lifetime. (...)