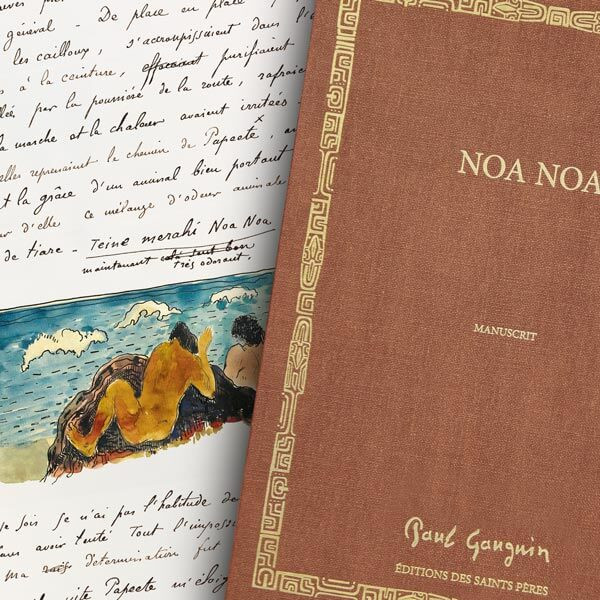

Noa Noa by Paul Gauguin

Terra Cotta edition,

numbered from 1 to 1,000

The incredible saga of the Noa Noa manuscripts

Paul Gauguin’s first trip to Tahiti in 1891 yielded some of his most famous paintings. It also conjured for him extraordinary sensations: perfumes, colours, chants… Although well-used to trips to remote places, the painter was dazzled, and attempted to capture some of these emotions in manuscript form. This extraordinary manuscript, at once legendary, long lost then found and subject to many adventures, is: the famous Noa Noa.

The mysterious front page does not give the reader any indication of the content, rather it prompts him to delve inside the book:

La forme sculpturale de là-bas

Deux colonnes d’un temple, simples et droites

Le grand Triangle de la Trinité

Le pouvoir d’en haut

Le Grand Taaroa existe, l’univers existe, le chaos de la volonté suprême, il les réunit.

What do these few words mean? And why is the beginning of the manuscript crossed out?

I do not know why the government gave me this assignment

probably to give the appearance of protecting an artist

I don't know why I made this trip with this piece of paper in my pocket?

The incredible story of the manuscript of Noa Noa conveniently reminds us of the central importance of autograph documents in understanding works and their artists. Though there were others that followed, Gauguin would have no doubt been happy to know that his first Noa Noa, the original manuscript, would survive him. In all its spontaneity and uneven beauty, this document is probably the one that best expresses the sense of heaven that the painter discovered on Earth.

Paul Gauguin, the traveller

What was Gauguin looking for as he moved incessantly from one place to another? Once upon a time, he would have replied “to live in the wild”. The idea of a ‘studio in the tropics’ took form in his mind, and, after having considered several destinations, he became obsessed with the notion of Tahiti as a symbol of tranquility far from civilization where he could indulge in his art without constraints. His approach was in no way attached to the past; he wanted to leap wholeheartedly into the future. In a letter to his wife Mette Gauguin in July 1890, he confided to her that he prayed for the day he could take refuge on an island to live a life of ecstasy, calm and art.

At the beginning of 1891, with the help of the poet Stéphane Mallarmé and the writer and critic Octave Mirbeau, Gauguin financed his trip by selling a group of his paintings at auction at Drouot. In April, he left Marseille to Papeete, where he arrived on 9 June. He immediately withdrew to Mataiea, an isolated village by the sea, where, animated with a new ardour, he began to paint like never before. This ‘man who paints men’, as he was known by the locals, blended into the landscape with relish. Unfortunately, illness forced him to return to France two years later. However, Tahiti did not leave his heart or spirit: he was certain that he would return.

The desire to write a book

Paul Gauguin had already done some writing, notably the illustrated volume Ancien culte mahorie. The work Noa Noa, which means ‘fragrant’, was to be a tribute to ‘all that Tahiti exudes’ – its light and fragrances, as well as providing a frame through which to understand his painting. The project began to take shape in the autumn of 1893.

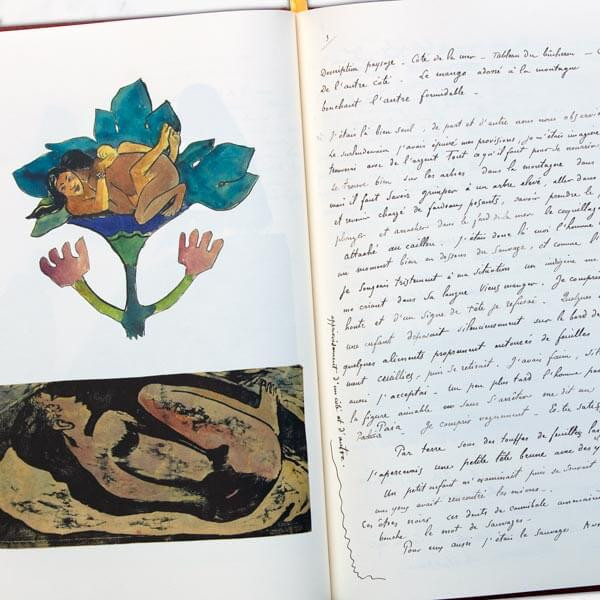

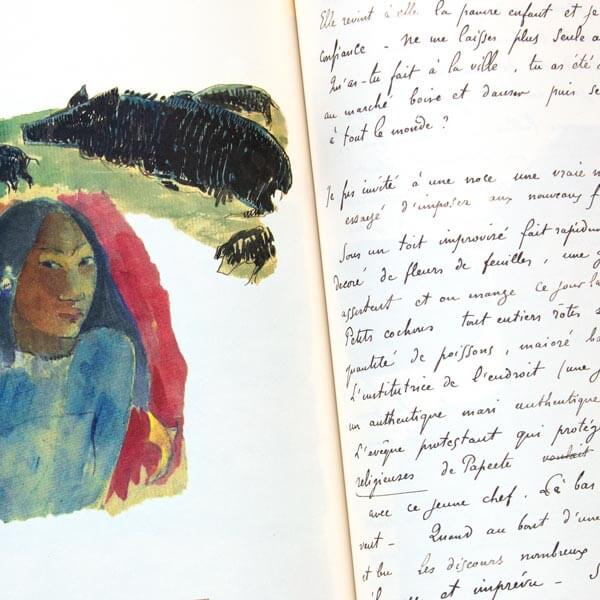

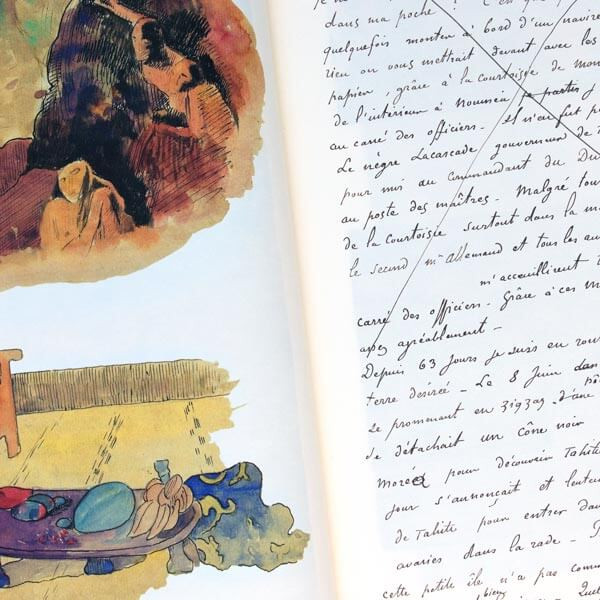

Combining memories of art with a new intensity of feeling, Paul Gauguin put to paper the tale of his paradise lost. He describes his arrival on the island and the funeral of the last king of Tahiti, Pomaré V; the village of Mataiea, five hours by cart from Papeete; his portrait “Vahiné no te tiare” (Woman with a flower)… In his writing, a play of light formed at his fingertips:

I began to work, take notes, make sketches of all kinds. Everything in the landscape blinded me, dazzled me. Coming from Europe, I was always uncertain about colour, searching from midday to two o’ clock: it was so easy to start applying red and blue to the canvas as a matter of course. Yet in the streams, forms of gold enchanted me. Why was I reluctant to pour all this gold and sunshine onto my canvas?

Paul Gauguin chronicles his life with the inhabitants of the island, an expedition in the forest in search of rosewood to carve, a memorable fishing trip… While it is certainly an elevation of Tahiti to the realm of the sublime, Gauguin himself didn’t seem concerned with accuracy. The manuscript runs over a few dozen sheets, with some crossings-out but nevertheless elegant, simple and remarkable. Still, Paul Gauguin didn’t fully believe in it. He was definitely a painter, but could he also be a writer?

Noa Noa, lost and found

The first manuscript, the subject of this facsimile, boasts an astonishing history. Paul Gauguin first entrusted it to Charles Morice, the poet with whom he collaborated to refine the work. Morice embellished it with poems and texts which distorted the initial project, resulting in a second manuscript, copied and taken by Gauguin to the Marquesas Islands during his last trip to Polynesia. This version is the most well-known because it was considered - mistakenly - as exclusively Gauguin’s own work. It served as the basis for a series of editions by various journals and publishers which were not approved by Paul Gauguin.

But what about our first manuscript? Despite Gauguin and Morice’s artistic differences, the latter held onto the precious bundle of pages. In 1908, Morice sold this treasured item – though it was not yet recognised as one – to the printmaker Edmond Sagot. The poet made Sagot promise to keep it secret, which signals both the importance of the document and Morice’s dubious ownership of Noa Noa. For years, the manuscript was hidden in a trunk in Sagot's attic. Following a move in 1937, Sagot’s daughter finally retrieved it and brought it to public attention in the 1950s. Since 1985 it has been in the collection of the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles.

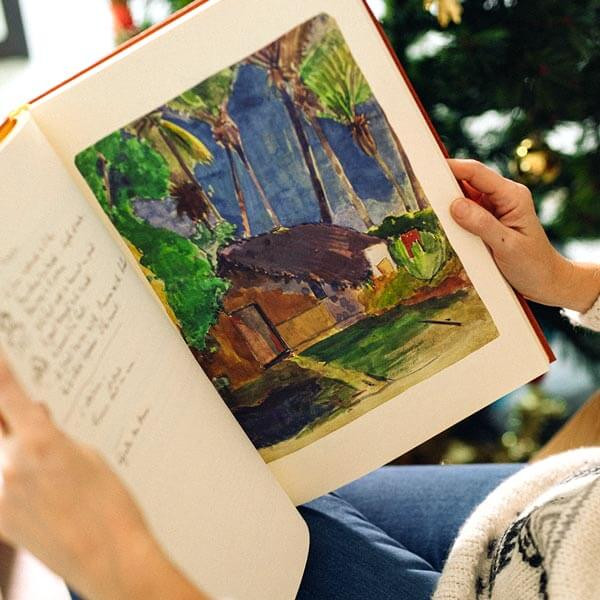

47 drawings and watercolors by Paul Gauguin

This facsimile is accompanied by a selection of drawings and watercolors from the second manuscript (Louvre, Paris).

With aknowledgment to David Haziot, Odile d'Harcourt, Leïla Jarbouai.

Sources:

- Isabelle Cahn (documentaliste du musée d’Orsay), Paul Gauguin, Noa Noa. ArtAbsolument n°6 (Paris, 2003).

- Armelle Fémelat, Gauguin. D’art et de liberté, éditions Beaux-Arts/Michel Lafon (Paris, 2017).

- Paul Gauguin, Noa Noa, édition de l’Association des Amis du Musée GAUGUIN à Tahiti et la « GAUGUIN and Oceania Foundation » à New York (Paris, 1988). Réalisé et présenté par Gilles Artur, Jean-Pierre Fourcade et Jean-Pierre Zing, traduction de John Donne.

- Paul Gauguin, Noa Noa. Ce qu’exhale Tahiti, éditions de l’Escalier (Saint-Didier, 2019).

- Paul Gauguin, Noa Noa. Notes et postface de Jérôme Vérain. Éditions Mille et une Nuits (Paris, 2002).

- David Haziot, Gauguin, Fayard (Paris, 2017).

- Jean-François Staszak, Géographies de Gauguin, éditions Bréal (Paris, 2003).

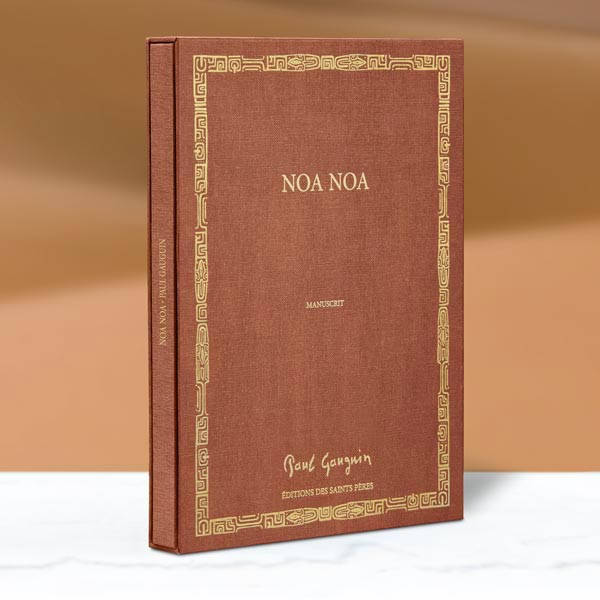

Deluxe edition

Numbered from 1 to 1,000, this Terra Cotta edition is presented in a large format handmade slipcase.

Printed with vegetal ink on eco-friendly paper, each book is bound and sewn using only the finest materials.

Mrs Dalloway: Thanks to a new reproduction of the only full draft of Mrs. Dalloway, handwritten in three notebooks and initially titled “The Hours,” we now know that the story she completed — about a day in the life of a London housewife planning a dinner party — was a far cry from the one she’d set out to write (...)

The Grapes of Wrath: The handwritten manuscript of John Steinbeck’s masterpiece The Grapes of Wrath, complete with the swearwords excised from the published novel and revealing the urgency with which the author wrote, is to be published for the first time. There are scarcely any crossings-out or rewrites in the manuscript, although the original shows how publisher Viking Press edited out Steinbeck’s dozen uses of the word “fuck”, in an attempt to make the novel less controversial. (...)

Jane Eyre: This is a book for passionate people who are willing to discover Jane Eyre and Charlotte Brontë's work in a new way. Brontë's prose is clear, with only occasional modifications. She sometimes strikes out words, proposes others, circles a sentence she doesn't like and replaces it with another carefully crafted option. (...)

The Jungle Book: Some 173 sheets bearing Kipling’s elegant handwriting, and about a dozen drawings in black ink, offer insights into his creative process. The drawings were not published because they are unfinished, essentially works in progress. (...)

The Lost World: SP Books has published a new edition of The Lost World, Conan Doyle’s 1912 landmark adventure story. It reproduces Conan Doyle’s original manuscript for the first time, and includes a foreword by Jon Lellenberg: "It was very exciting to see, page by page, the creation of Conan Doyle’s story. To see the mind of the man as he wrote it". Among Conan Doyle’s archive, Lellenberg made an extraordinary discovery – a stash of photographs of the writer and his friends dressed as characters from the novel, with Conan Doyle taking the part of its combustible hero, Professor Challenger. (...)

Frankenstein: There is understandably a burst of activity surrounding the book’s 200th anniversary. The original, 1818 edition has been reissued, as paperback by Penguin Classics. There’s a beautifully illustrated hardcover, “The New Annotated Frankenstein” (Liveright) and a spectacular limited edition luxury facsimile by SP Books of the original manuscript in Shelley's own handwriting based on her notebooks. (...)

The Great Gatsby: But what if you require a big sumptuous volume to place under the tree? You won’t find anything more breathtaking than SP Books ’s facsimile of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s handwritten manuscript of The Great Gatsby, showing the deletions, emendations and reworked passages that eventually produced an American masterpiece (...)

Oliver Twist: In the first ever facsimile edition of the manuscript SP Books celebrates this iconic tale, revealing largely unseen edits that shed new light on the narrative of the story and on Dickens’s personality. Heavy lines blocking out text are intermixed with painterly arabesque annotations, while some characters' names are changed, including Oliver’s aunt Rose who was originally called Emily. The manuscript also provides insight into how Dickens censored his text, evident in the repeated attempts to curb his tendency towards over-emphasis and the use of violent language, particularly in moderating Bill Sikes’s brutality to Nancy. (...)

Peter Pan: It is the manuscript of the latter, one of the jewels of the Berg Collection in the New York Public Library, which is reproduced here for the first time. Peter’s adventures in Neverland, described in Barrie’s small neat handwriting, are brought to life by the evocative color plates with which the artist Gwynedd Hudson decorated one of the last editions to be published in Barrie’s lifetime. (...)