Paradise Lost by John Milton

Sky blue edition,

numbered from 1 to 1,000

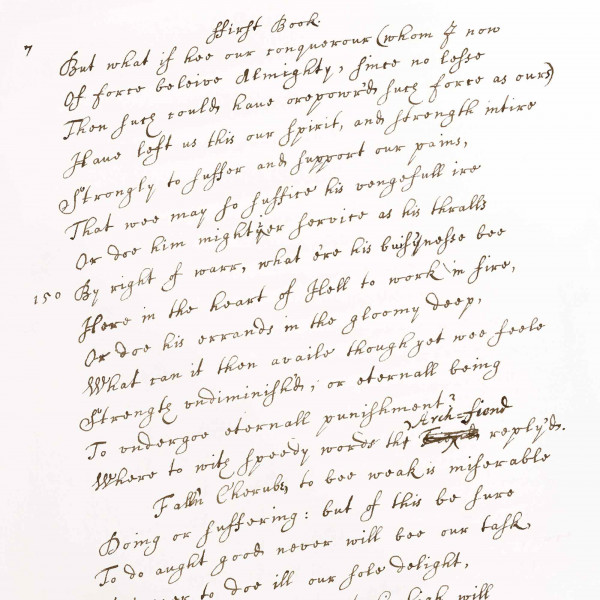

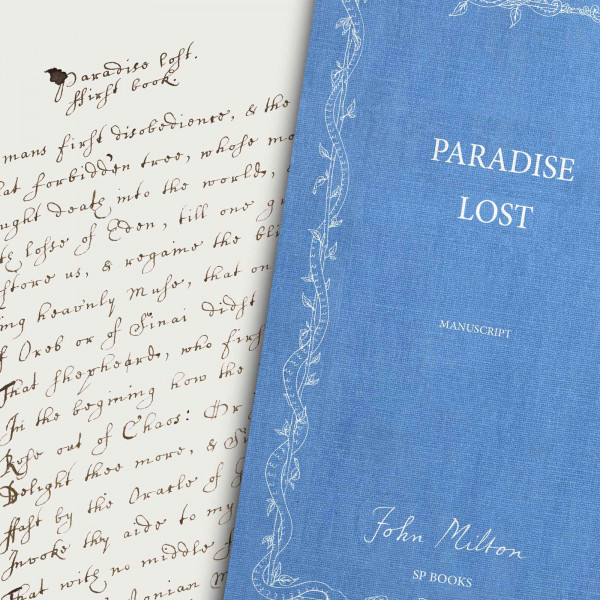

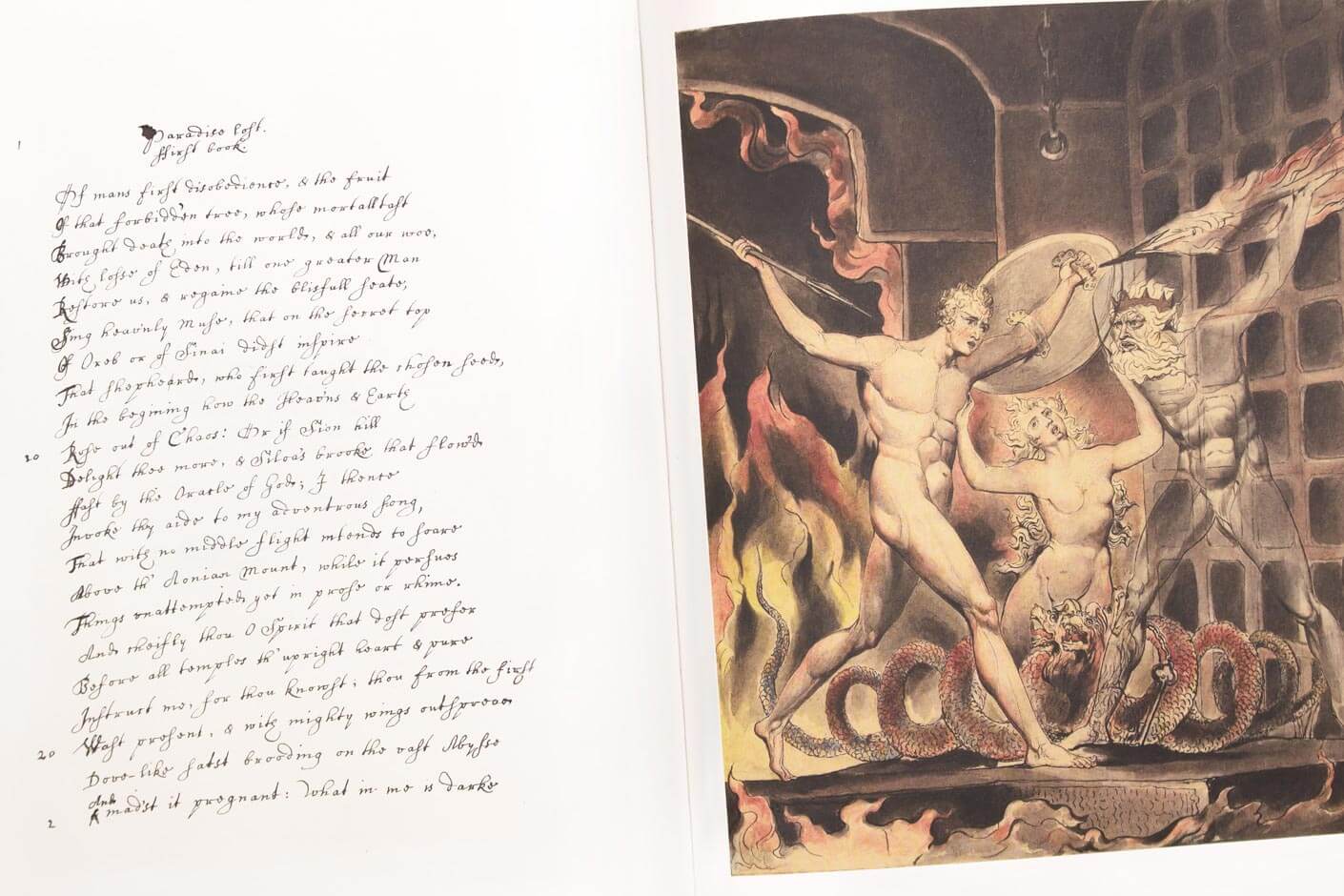

Paradise Lost, Book I, the only surviving manuscript

Some texts are the life work of an author: that is the case with John Milton's Paradise Lost, a poem of ten thousand lines, divided into ten books, and published in 1667 to become a Bible of the Romantic movement and of generations of writers and readers through the centuries since. A second edition appeared in 1674 with the poem rearranged into twelve books and with minor revisions.

One is able to imagine a John Milton between fifty and sixty years old, blind, retired from the public life, a recluse, dedicated to studying and writing, reading to himself out loud, probably in a dark room:

Of that forbidden tree whose mortal taste

Brought death into the World, and all our woe,

With loss of Eden, till one greater Man

Restore us, and regain the blissful seat,

Sing, Heavenly Muse, that, on the secret top

Of Oreb, or of Sinai, didst inspire

That shepherd who first taught the chosen seed

In the beginning how the heavens and earth

Rose out of Chaos: or, if Sion hill

Delight thee more, and Siloa’s brook that flowed

Fast by the oracle of God, I thence

Invoke thy aid to my adventurous song,

That with no middle flight intends to soar

Above th’ Aonian mount, while it pursues

Things unattempted yet in prose or rhyme.

…

The first Book, the only surviving manuscript from near on five centuries, narrates the events following man’s disobedience and resultant fall from Paradise. The cause? The despised serpent of course, Satan, who incites an insurrection against God, accompanied by his legions of dark angels. Despite his best efforts, Satan is cast out from Heaven and condemned to Hell. This place haunted by shadows, called Chaos, is where the Devil awakes in confusion finding himself exiled amongst lost souls.

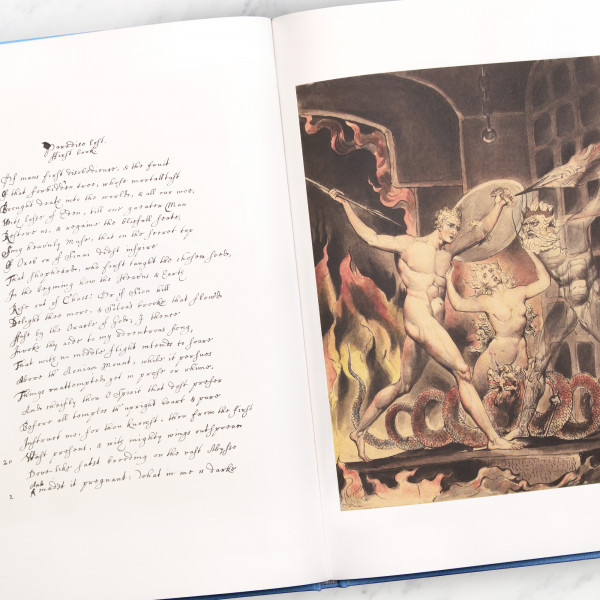

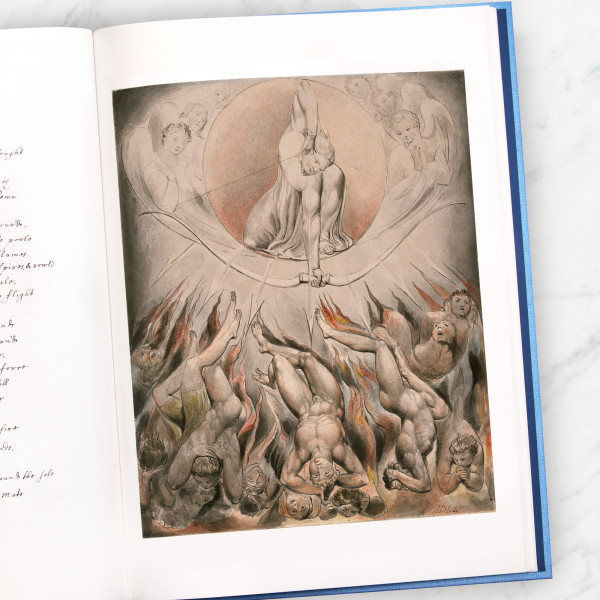

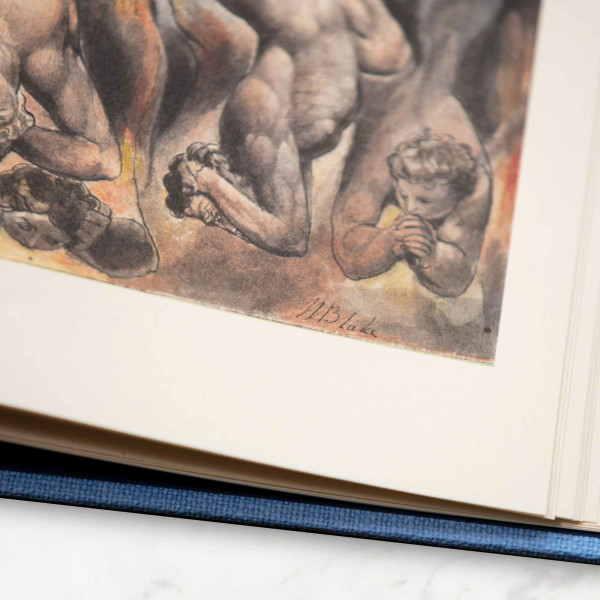

With paintings by William Blake

He calls upon his most trusted lieutenant in crime, Belzebuth; he assembles and galvanizes his evil hosts. With promises of a new Heaven he puts his legions on a war footing. In Pandæmonium, capital of Hell, Satan convenes a council of demons.

Published in book form for the first time

Born in 1608, Milton attended the prestigious schools - St Paul's in London, Christ's College in Cambridge. A brilliant but tumultuous student, he began writing at the tender age of ten. His early work consisted mainly of poems in latin and letters in English prose. His first poem was published in 1632.

The germ of the idea that became Paradise Lost seems to have been in Milton's mind from about 1640. Evidence for this is the existence of drafts of a verse tragedy to be titled Adam Unparadised. Milton was then 32 years old: his pamphlets supporting civil and religious liberty had already given him a prominent political profile and after the Civil War he was to flourish at the heart of Cromwell's Commonwealth government. In private life, he wrote and suffered an unhappy marriage, as well as weakening eyesight.

The Restoration marked the end of two decades of public service. Milton's writings were condemned, and in 1660 he was even briefly imprisoned. Thenceforth he devoted himself to scholarly study and his writing. Completely blind since 1652, supported by his third wife - the previous ones had died in childbirth - and his daughters, Milton saw his health steadily decline. He nevertheless continued with his great poem, composing out loud, memorising the lines and then dictating them to members of his family, as well as friends such as the poet Andrew Marvell.

A collective work

The resulting manuscript of Paradise Lost is therefore a collective work. Milton was in the habit of composing in bed, at night or early in the morning. According to contemporary witnesses he then 'sat leaning backward obliquely in an easy chair, with his leg flung over the elbow of it' to dictate the results, verbally correcting the transcripts as they were read back to him by his amanuenses.

With illustrations by William Blake

The present fragment of manuscript is the only surviving witness of the creative process behind Paradise Lost, and corresponds to Book I of the poem. It consists of 33 numbered pages and appears to be a fair copy by a professional scribe, compiled from drafts supplied by Milton's various helpers. Supervised by Milton, corrections to the manuscript are present in five different hands. It was used for the first edition of the poem in October or November 1667 and on the first page it bears the imprimatur (let it be printed) of the “Stationers’”*, then necessary in order to print and publish a book: Let it be printed. Thomas Tomkyns, one of the religious servants of the most reverent father and lord in Christ, Lord Gilbert, by divine providence archbishop of Canterbury. Richard Royston. Entered by George Tokefield, clerk.

Although finished in 1665, Paradise Lost did not appear until two years later, due to the combination of a paper shortage resulting from the Second Anglo-Dutch War; an outbreak of plague; and the Great Fire of London. Its publisher, Samuel Simmons, bought it for £5**, and printed 1300 copies of the first edition selling them for 3 shillings each. His contract with Milton, the first of its kind between an author and editor, stipulated that Simmons should pay a further £5 on publication.

A treasure held at the Morgan library (New York)

The manuscript was sold by Simmons to the bookseller Brabazon Aylmer for £25, then passed through various hands before its acquisition by J. Pierpont Morgan at Sotheby’s in London in 1904. It is now in the Morgan Library & Museum in New York.

Paradise Lost has inspired generations of writers, among them John Keats, George Eliot, Thomas Hardy, as well as musicians such as Haendel and Haydn. Our modern language still uses neologisms forged by Milton in Paradise Lost such as ‘dreary’, ‘pandæmonium’, ‘acclaim’, ‘rebuff’, ‘self-esteem’, ‘unaided’, ‘impassive’, ‘enslaved’, ‘jubilant’, ‘serried’, ‘solaced’, ‘satanic’…

With grateful acknowledgement to Philip Palmer and Ken Page.

Notes:

* The Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers is the corporation of paper makers, printers and publishers of the City of London. Founded in 1403, it remains active although its role is now purely advisory.

** £5 in 1667 is £1,227 at 2020 prices according to the Bank of England inflation calculator. Three shillings would be roughly £50 today.

Sources:

- Gordon Campbell, Milton, John (1608–1674), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press (2004).

- François-René de Chateaubriand, Le Paradis perdu suivi de Essai sur la littérature anglaise, Garnier (Paris, 1876).

- Armand Himy, Milton, Fayard, Paris (2003).

- John Keats, The Complete Poems, Penguin Classics, London (1988).

- Barbara Lewalski, The Life of John Milton, London (Wiley–Blackwell).

- John Milton, Paradise Lost, printed at the Lyceum Press Liverpool and published by the Liverpool Booksellers' Co. Limited 4to (London, 1906).

- Websites: The Morgan Library, Keats House Museum, The Open University UK (record 17367), Museum Crush (Keats' copy of Paradise Lost)

Deluxe edition

Numbered from 1 to 1,000,

this Sky Blue edition is presented

in a large format handmade slipcase.

Printed with vegetal ink on

eco-friendly paper, each book is

bound using the finest materials.

Mrs Dalloway: Thanks to a new reproduction of the only full draft of Mrs. Dalloway, handwritten in three notebooks and initially titled “The Hours,” we now know that the story she completed — about a day in the life of a London housewife planning a dinner party — was a far cry from the one she’d set out to write (...)

The Grapes of Wrath: The handwritten manuscript of John Steinbeck’s masterpiece The Grapes of Wrath, complete with the swearwords excised from the published novel and revealing the urgency with which the author wrote, is to be published for the first time. There are scarcely any crossings-out or rewrites in the manuscript, although the original shows how publisher Viking Press edited out Steinbeck’s dozen uses of the word “fuck”, in an attempt to make the novel less controversial. (...)

Jane Eyre: This is a book for passionate people who are willing to discover Jane Eyre and Charlotte Brontë's work in a new way. Brontë's prose is clear, with only occasional modifications. She sometimes strikes out words, proposes others, circles a sentence she doesn't like and replaces it with another carefully crafted option. (...)

The Jungle Book: Some 173 sheets bearing Kipling’s elegant handwriting, and about a dozen drawings in black ink, offer insights into his creative process. The drawings were not published because they are unfinished, essentially works in progress. (...)

The Lost World: SP Books has published a new edition of The Lost World, Conan Doyle’s 1912 landmark adventure story. It reproduces Conan Doyle’s original manuscript for the first time, and includes a foreword by Jon Lellenberg: "It was very exciting to see, page by page, the creation of Conan Doyle’s story. To see the mind of the man as he wrote it". Among Conan Doyle’s archive, Lellenberg made an extraordinary discovery – a stash of photographs of the writer and his friends dressed as characters from the novel, with Conan Doyle taking the part of its combustible hero, Professor Challenger. (...)

Frankenstein: There is understandably a burst of activity surrounding the book’s 200th anniversary. The original, 1818 edition has been reissued, as paperback by Penguin Classics. There’s a beautifully illustrated hardcover, “The New Annotated Frankenstein” (Liveright) and a spectacular limited edition luxury facsimile by SP Books of the original manuscript in Shelley's own handwriting based on her notebooks. (...)

The Great Gatsby: But what if you require a big sumptuous volume to place under the tree? You won’t find anything more breathtaking than SP Books ’s facsimile of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s handwritten manuscript of The Great Gatsby, showing the deletions, emendations and reworked passages that eventually produced an American masterpiece (...)

Oliver Twist: In the first ever facsimile edition of the manuscript SP Books celebrates this iconic tale, revealing largely unseen edits that shed new light on the narrative of the story and on Dickens’s personality. Heavy lines blocking out text are intermixed with painterly arabesque annotations, while some characters' names are changed, including Oliver’s aunt Rose who was originally called Emily. The manuscript also provides insight into how Dickens censored his text, evident in the repeated attempts to curb his tendency towards over-emphasis and the use of violent language, particularly in moderating Bill Sikes’s brutality to Nancy. (...)

Peter Pan: It is the manuscript of the latter, one of the jewels of the Berg Collection in the New York Public Library, which is reproduced here for the first time. Peter’s adventures in Neverland, described in Barrie’s small neat handwriting, are brought to life by the evocative color plates with which the artist Gwynedd Hudson decorated one of the last editions to be published in Barrie’s lifetime. (...)