Der Steppenwolf by Hermann Hesse

Perl grey edition,

numbered from 1 to 1,000,

The Steppenwolf, Hermann Hesse's manuscript

Published in 1927, The Steppenwolf portrays the inner turmoil of a human soul caught between the impulses to savagery and polite society. Its masterful structure and the intensity of its writing made it a cult novel in the USA during the 1970s.

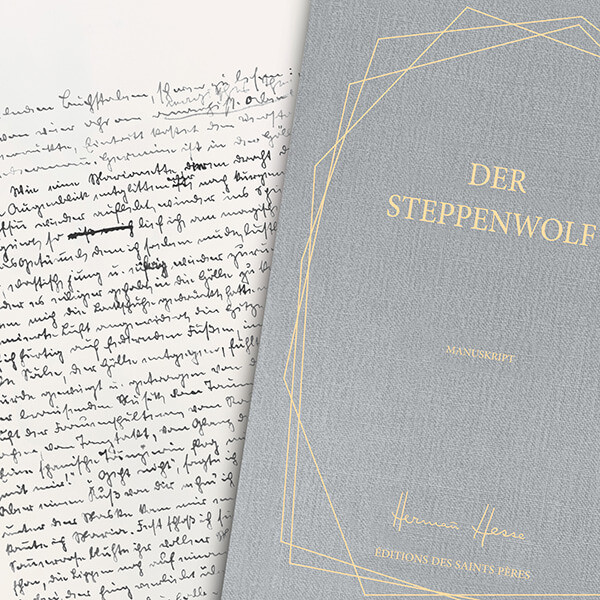

The Manuscript is composed of 155 pages, most of which are handwritten. After Hermann Hesse’s death in 1962, his widow Ninon donated part of her husband’s literary collection – consisting of manuscripts and letters – to the German Literature Archive in Marbach (Deutsches Literaturarchiv).

The Deutsches Literaturarchiv, founded in 1955 in Marbach am Neckar, Germany, is one of the most important literary archives in the world. This prestigious institution founded the Museum of Modern Literature in 2006.

An exploration of an inner crisis

In the early 1920s, Hermann Hesse was approaching his fifties. Having started as a bookseller, following the literary success of Peter Camenzind (published 1904), he was able to make a living from his writing, which freed him to indulge his passion for travel. However, he was not without problems – his anti-militarism earned him violent public opposition in Germany, as well as the death of his father, his ex-wife Mia Bernouilli’s schizophrenia, concerns over his sons’ education and a growing sense of failure in his second marriage to the singer Ruth Wenger. Added to his own health worries, these plunged him into a deep and lasting existential crisis.

During this period, Hermann Hesse wrote the autobiographical texts Crisis; Pages from a Diary (1922) and A Guest at the Spa (1925). In the winter of 1926 in Zurich he began to composes a series known as the ‘Krisis poems’, some of which appeared in the literary review Die neue Rundschau under the title The Steppenwolf. The great novel as it is known today was slowly forming on the page.

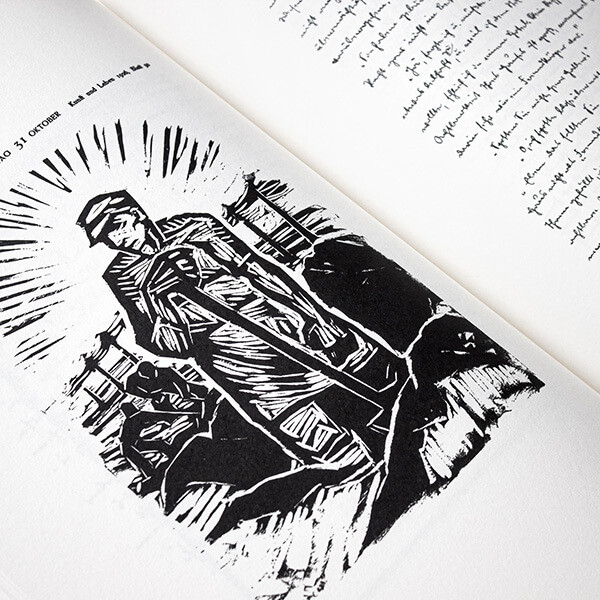

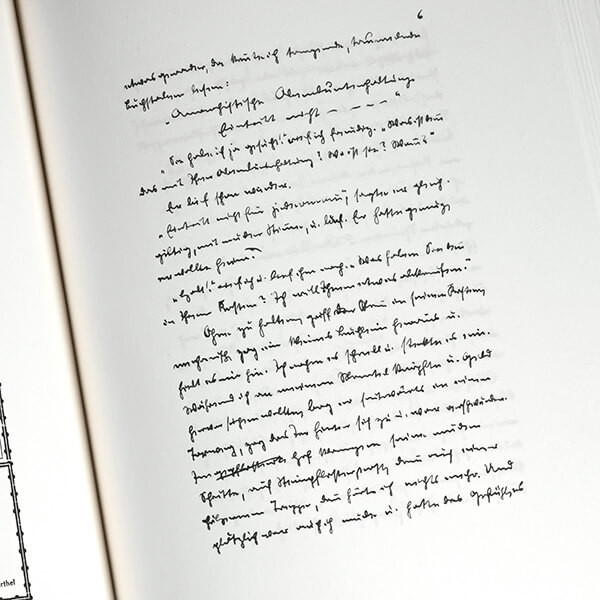

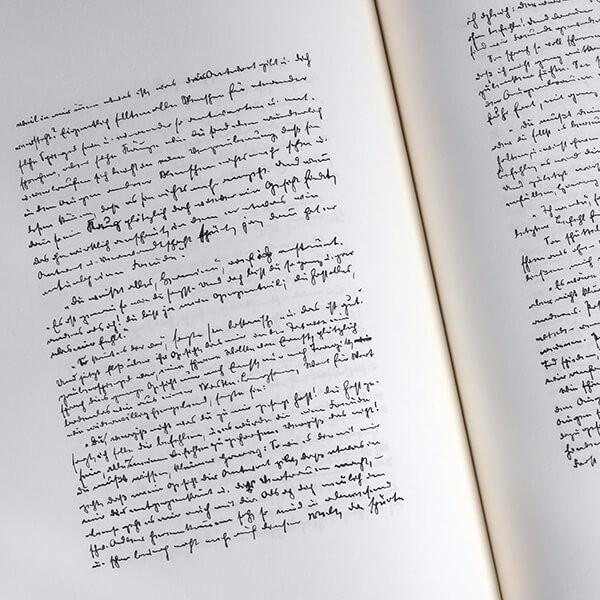

A manuscript of many layers

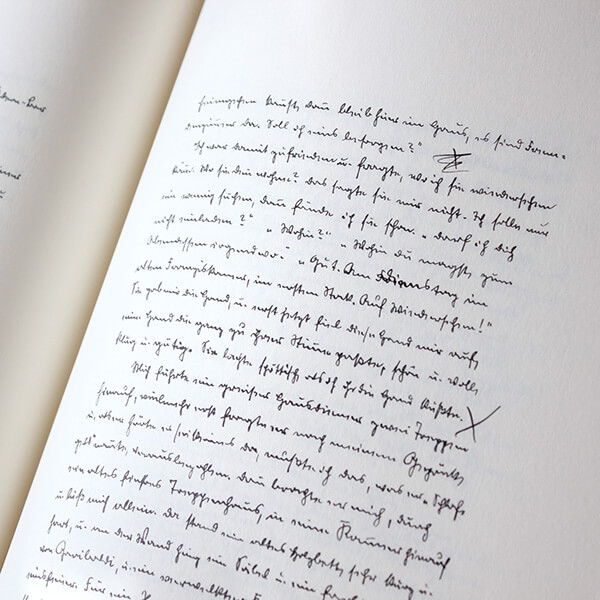

The majority of the sheets are covered with writing in blue or black ink on gridded paper, and folded in half so that each sheet forms a set of four pages. The pages are hand-numbered using Arabic or Roman numerals. Hermann Hesse added extra sheets during the proofreading stage, marking an ‘X’ on the original sheets to show where they were to be inserted. These additional sheets were often written on scrap paper, such as publishers’ announcements, letters, watercolours or old calendar pages, the backs of which he covered in writing – all of which are reproduced here in the chronology of the novel.

‘For example, part of the passage mentioning Hermine’s faith in saints, including St. Francis of Assisi, is penned on the back of a calendar page spanning the weeks 1-6 November 1926,’ explains the specialist Rudolf Probst in his preface to this edition (see below).

To this corpus, the writer also included elements written before the novel existed. These include the episode entitled ‘Goethe’s Dream’, which was published on 12 September 1926 in the daily newspaper Frankfurter Zeitung.

A foreword by Rudolf Probst

Rudolf Probst studied German and philosophy at the University of Bern, where he was awarded a doctorate in 2004 for his work on the Swiss author Friedrich Dürenmatt. Since 1993 he has worked at the Swiss Literary Archives in Bern – first as a research assistant, then as Head of Indexing – where he works with the estates and archives of Peter Bichsel, Hans Boesch, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Hermann Hesse, Carl Albert Loosli, Golo Mann, Klaus Merz and Hansjörg Schertenleib.

His most recent publication is: Friedrich Dürrenmatt: Das Stoffe-Projekt. Textgenetische Edition in fünf Bänden. Verbunden mit einer erweiterten Online-Version. Aus dem Nachlass herausgegeben von Ulrich Weber und Rudolf Probst. Diogenes Verlag, Zürich, 2021.

Extract from the foreword:

'The genesis of a text often provides an interesting source of information for its analysis and interpretation: here, the physical appearance of the documents, both manuscripts and typescripts, reveal key elements to understand the work. For this reason, it seems worthwhile to describe this first version of The Steppenwolf, located in the Hermann Hesse Archive (Deutsches Literaturarchiv in Marbach). (...)

The manuscript begins with Hesse's preliminary remark on the Traktat (Treatise), found on the back of a letter from Dr. E. Leutenegger dated April 23, 1924: "This text will be highlighted in print by a stapled colored envelope with its own pagination, possibly also by a different type size". And indeed, in the first edition, the Treatise is separated from the rest of the text with a yellow envelope and an independant pagination. (…)

From the first fragments, poems and various variations of the manuscript, to the published novel, The Steppenwolf almost appears as a work of art, in which all the parts are interdependent. (...)'

With grateful thanks to Rudolf Probst, Vincent Yersin, Marc Meier-Maletz, Surhkamp, and the Hermann Hesse Estate.

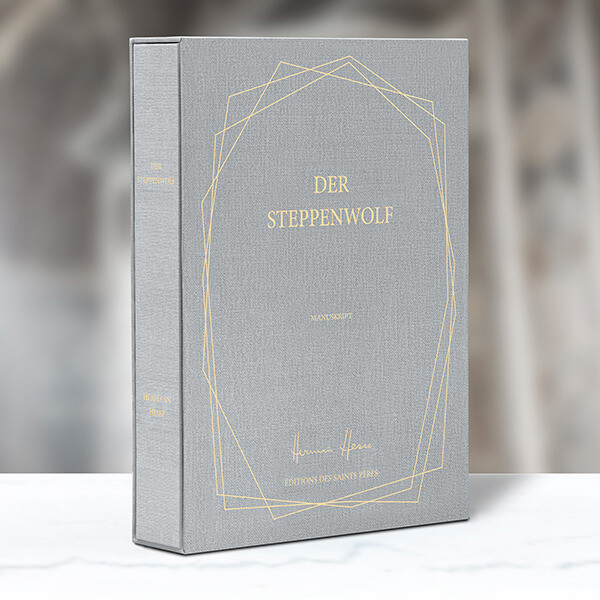

Deluxe edition

Numbered from 1 to 1,000,

this perl grey edition is presented

in a large format handmade slipcase.

Printed with vegetal ink on

eco-friendly paper, each book is

bound using the finest materials.

Mrs Dalloway: Thanks to a new reproduction of the only full draft of Mrs. Dalloway, handwritten in three notebooks and initially titled “The Hours,” we now know that the story she completed — about a day in the life of a London housewife planning a dinner party — was a far cry from the one she’d set out to write (...)

The Grapes of Wrath: The handwritten manuscript of John Steinbeck’s masterpiece The Grapes of Wrath, complete with the swearwords excised from the published novel and revealing the urgency with which the author wrote, is to be published for the first time. There are scarcely any crossings-out or rewrites in the manuscript, although the original shows how publisher Viking Press edited out Steinbeck’s dozen uses of the word “fuck”, in an attempt to make the novel less controversial. (...)

Jane Eyre: This is a book for passionate people who are willing to discover Jane Eyre and Charlotte Brontë's work in a new way. Brontë's prose is clear, with only occasional modifications. She sometimes strikes out words, proposes others, circles a sentence she doesn't like and replaces it with another carefully crafted option. (...)

The Jungle Book: Some 173 sheets bearing Kipling’s elegant handwriting, and about a dozen drawings in black ink, offer insights into his creative process. The drawings were not published because they are unfinished, essentially works in progress. (...)

The Lost World: SP Books has published a new edition of The Lost World, Conan Doyle’s 1912 landmark adventure story. It reproduces Conan Doyle’s original manuscript for the first time, and includes a foreword by Jon Lellenberg: "It was very exciting to see, page by page, the creation of Conan Doyle’s story. To see the mind of the man as he wrote it". Among Conan Doyle’s archive, Lellenberg made an extraordinary discovery – a stash of photographs of the writer and his friends dressed as characters from the novel, with Conan Doyle taking the part of its combustible hero, Professor Challenger. (...)

Frankenstein: There is understandably a burst of activity surrounding the book’s 200th anniversary. The original, 1818 edition has been reissued, as paperback by Penguin Classics. There’s a beautifully illustrated hardcover, “The New Annotated Frankenstein” (Liveright) and a spectacular limited edition luxury facsimile by SP Books of the original manuscript in Shelley's own handwriting based on her notebooks. (...)

The Great Gatsby: But what if you require a big sumptuous volume to place under the tree? You won’t find anything more breathtaking than SP Books ’s facsimile of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s handwritten manuscript of The Great Gatsby, showing the deletions, emendations and reworked passages that eventually produced an American masterpiece (...)

Oliver Twist: In the first ever facsimile edition of the manuscript SP Books celebrates this iconic tale, revealing largely unseen edits that shed new light on the narrative of the story and on Dickens’s personality. Heavy lines blocking out text are intermixed with painterly arabesque annotations, while some characters' names are changed, including Oliver’s aunt Rose who was originally called Emily. The manuscript also provides insight into how Dickens censored his text, evident in the repeated attempts to curb his tendency towards over-emphasis and the use of violent language, particularly in moderating Bill Sikes’s brutality to Nancy. (...)

Peter Pan: It is the manuscript of the latter, one of the jewels of the Berg Collection in the New York Public Library, which is reproduced here for the first time. Peter’s adventures in Neverland, described in Barrie’s small neat handwriting, are brought to life by the evocative color plates with which the artist Gwynedd Hudson decorated one of the last editions to be published in Barrie’s lifetime. (...)