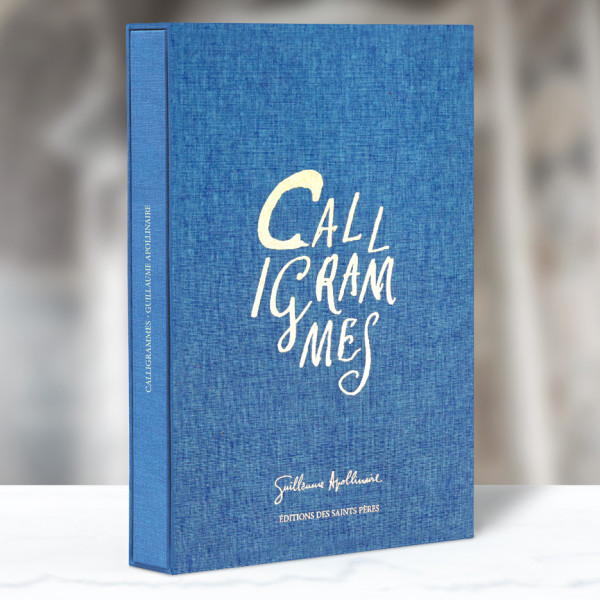

Calligrammes by Guillaume Apollinaire

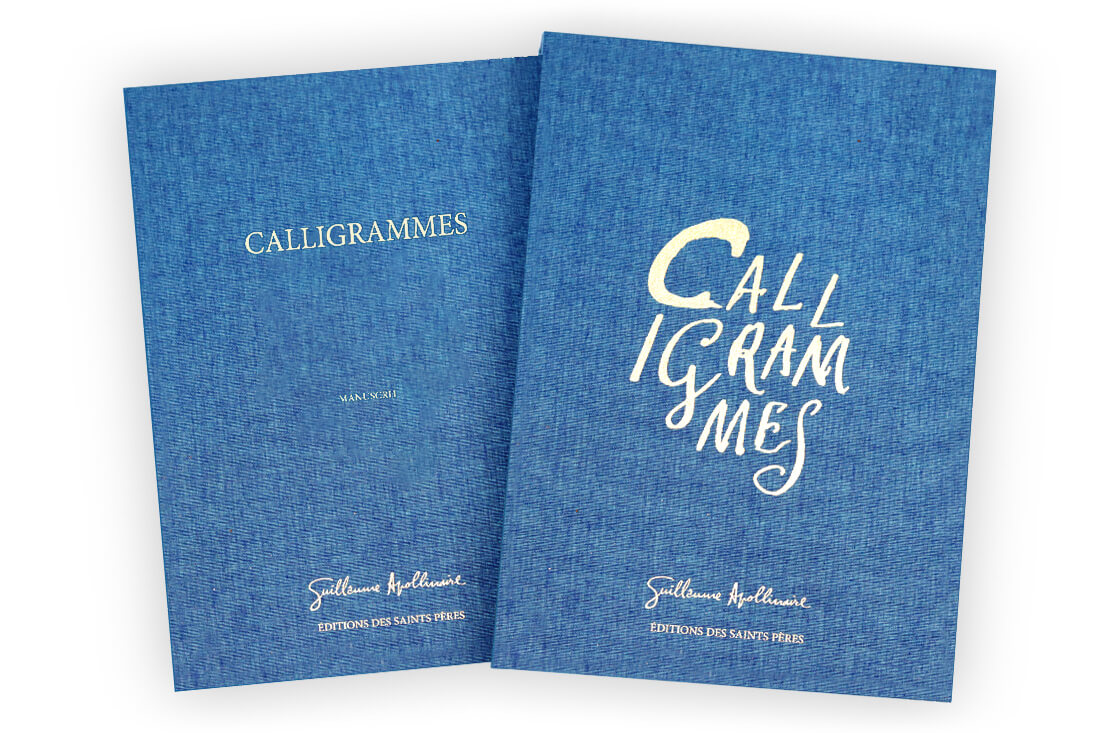

Petrol blue edition,

Numbered from 1 to 1000,

French edition

French edition (14x10")

Calligrammes - Guillaume Apollinaire's manuscripts - Poems of peace and war 1913-1916

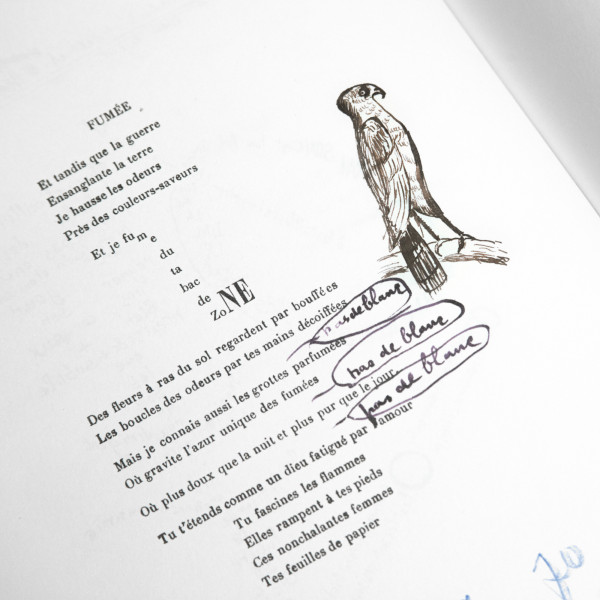

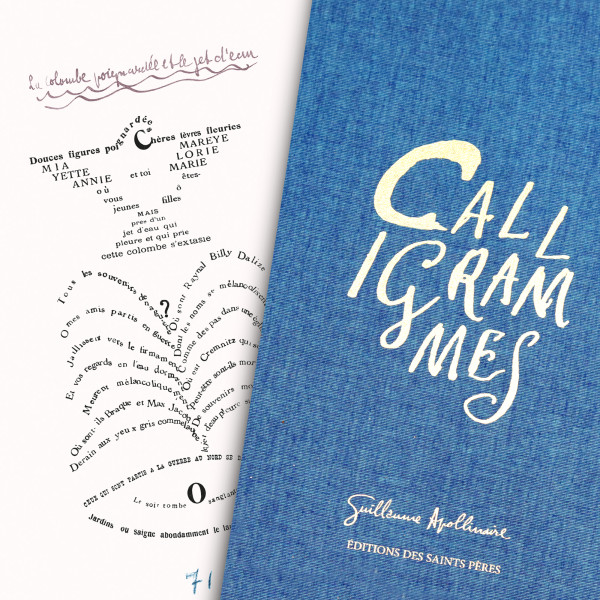

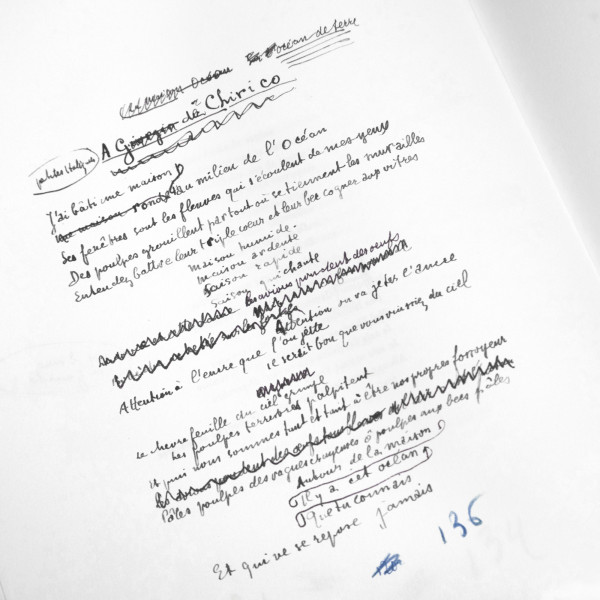

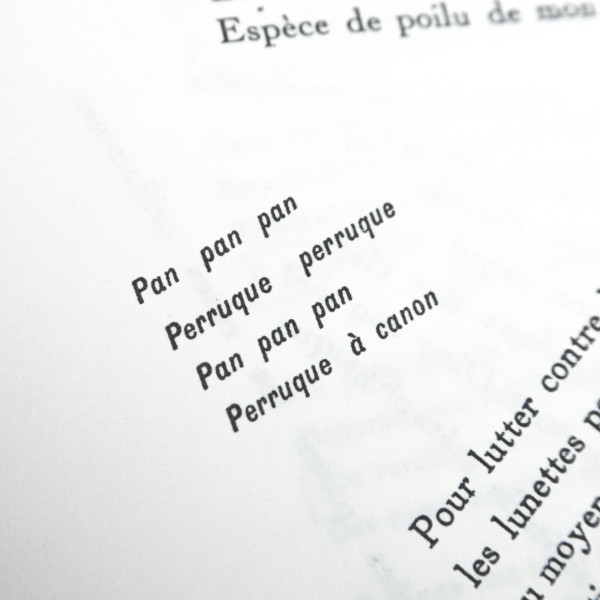

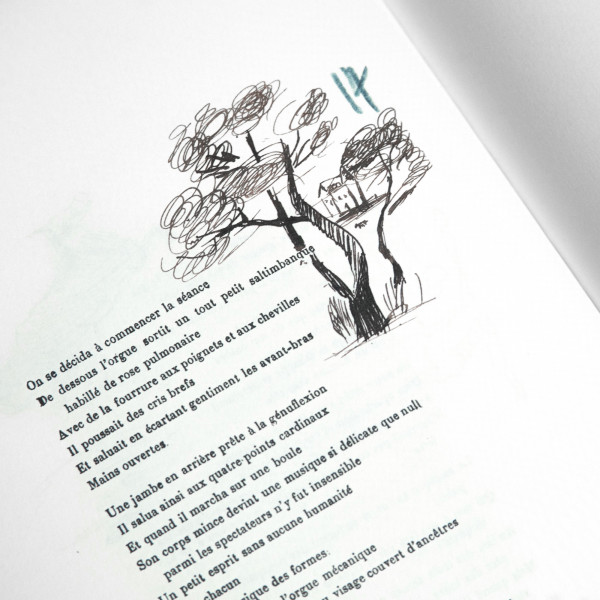

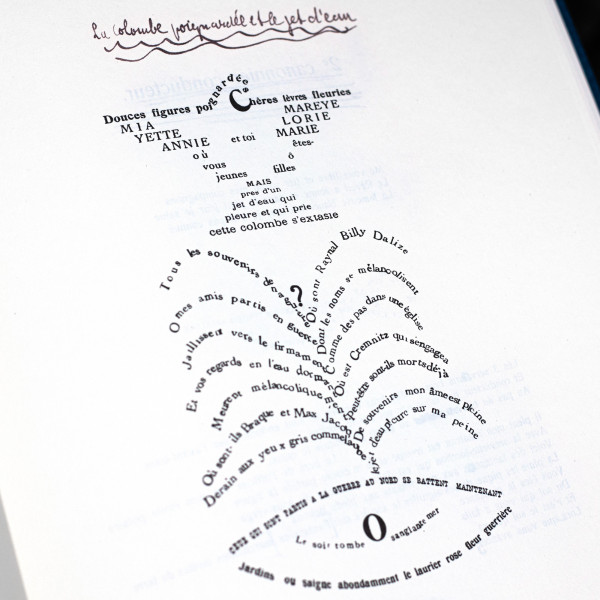

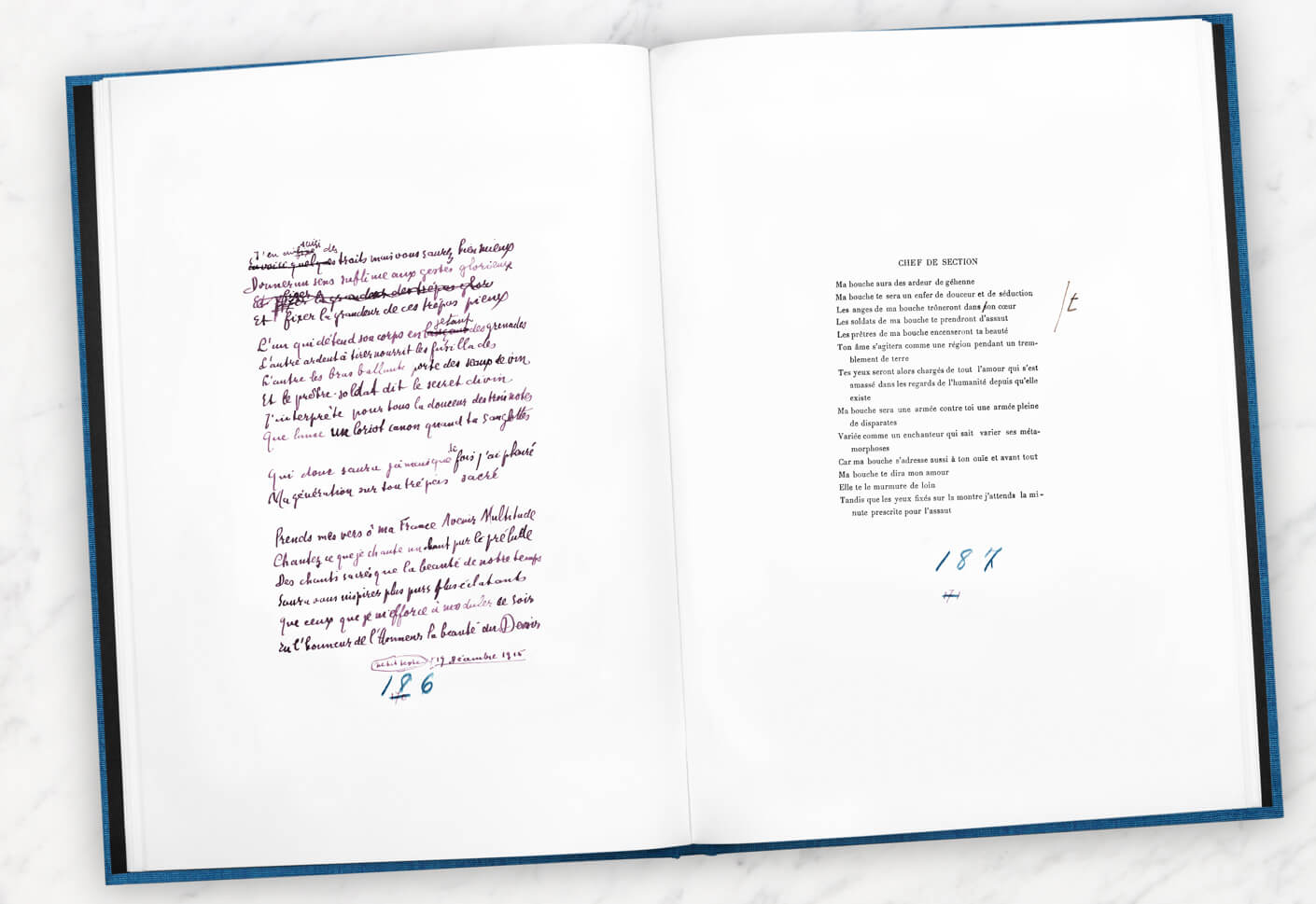

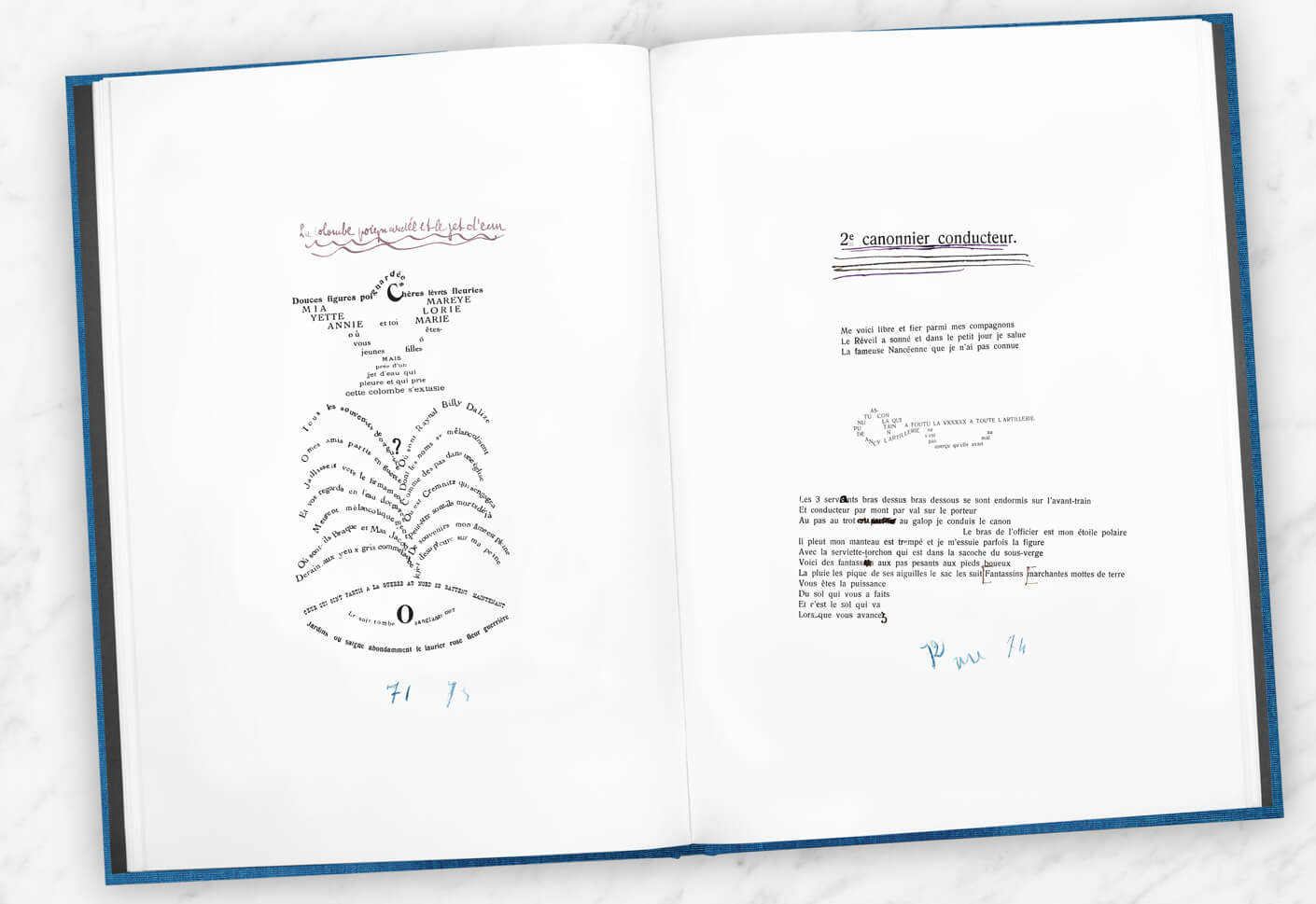

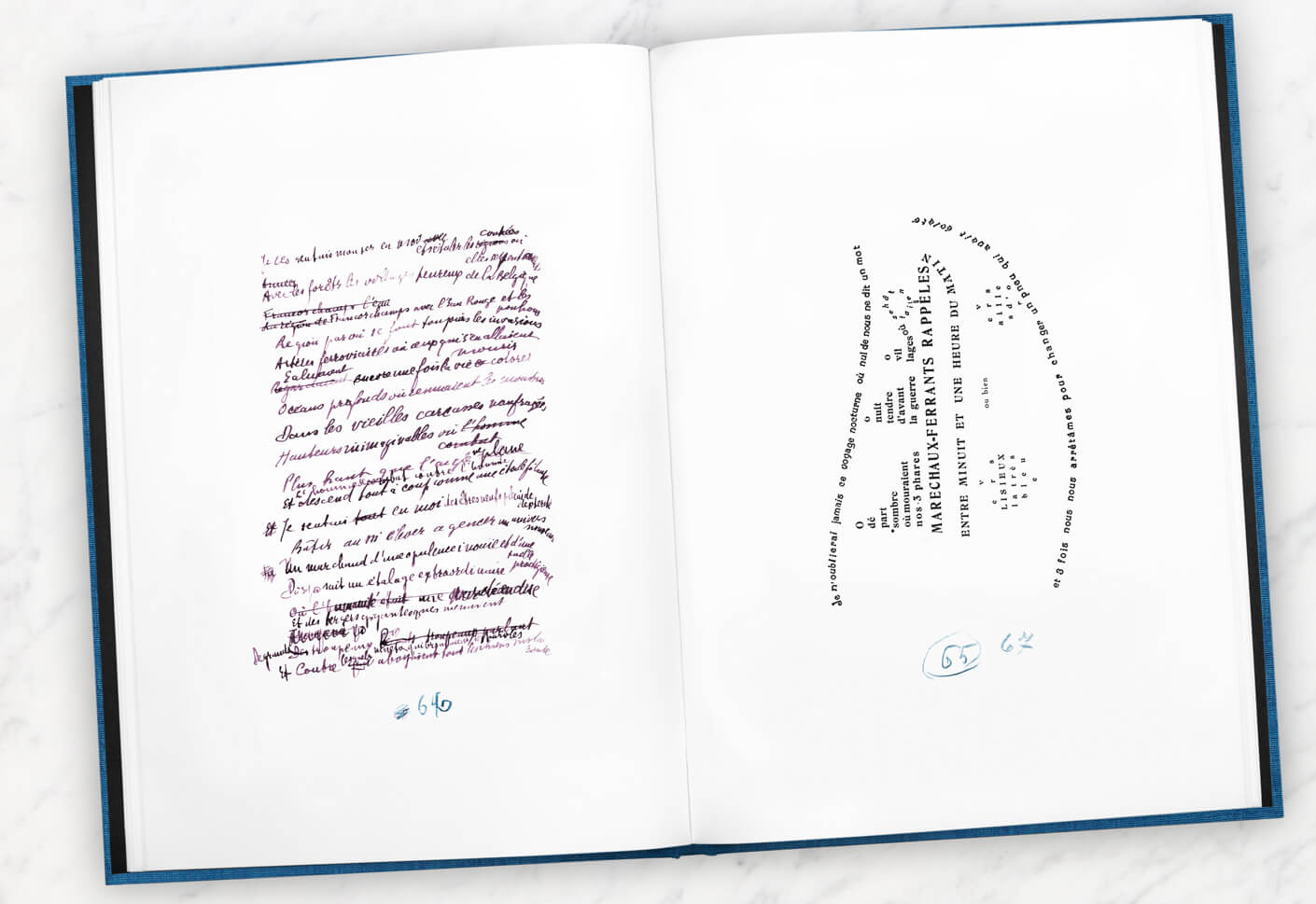

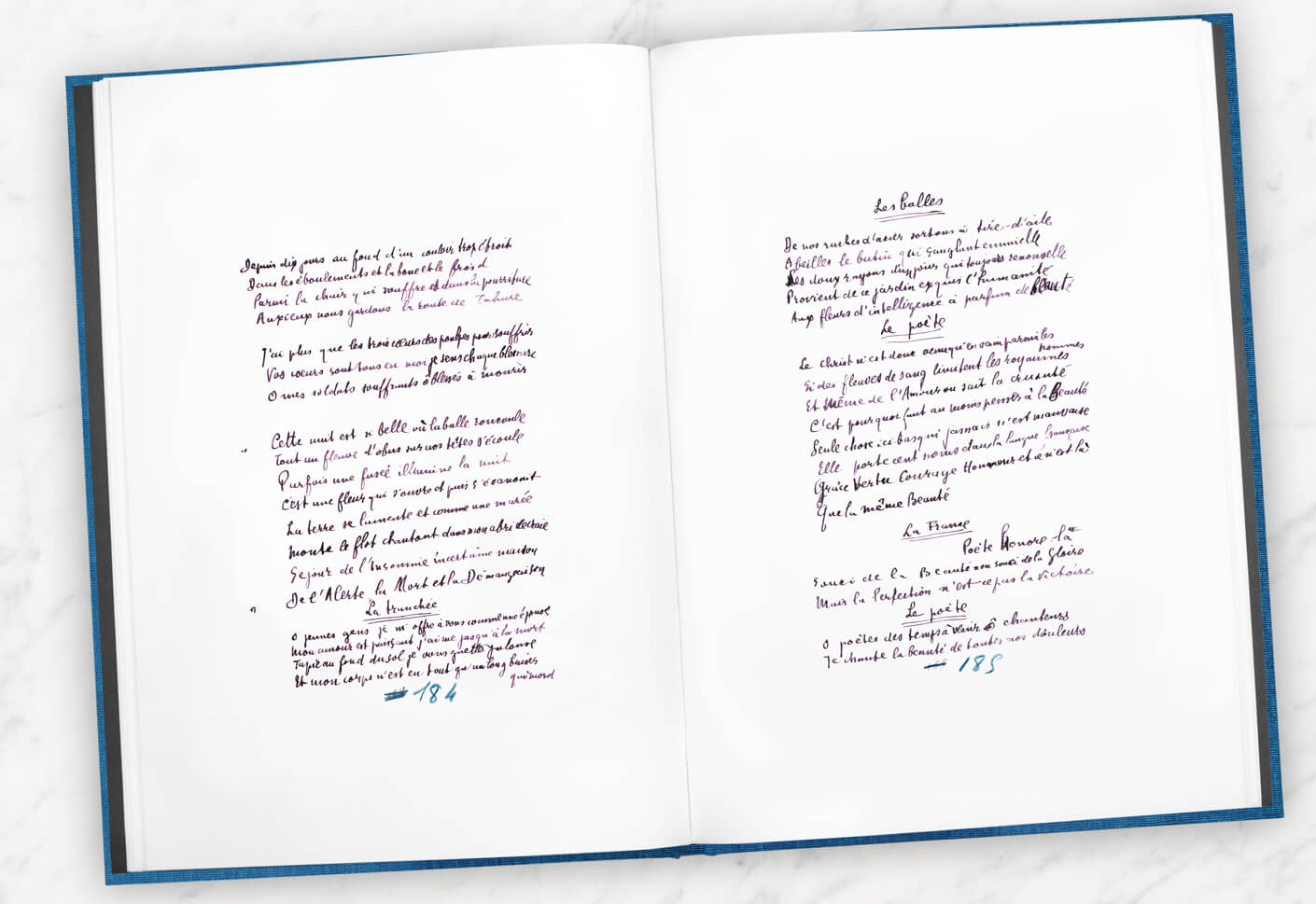

Typewritten pages corrected by hand, cut and pasted onto larger sheets; signatures in purple ink; assemblages of letters, drawings, annotations, retouches, a dedication, a biography and even a hand-drawn colophon… such is the abundance of creativity at work in the composition of Calligrammes: Poems of Peace and War 1913-1916.

Calligrammes, a remarkable maquette made up of written and typed pages, conserved at the Jacques Doucet Library

This incredible document of nearly 200 pages shows the working maquette composed by Guillaume Apollinaire in order to establish the near definitive version of the collection, whose look and feel oscillates somewhere between a workman’s toolbox and a wondrous treasure chest. The document is held at the BLJD (Bibliothèque littéraire Jacques Doucet, Paris).

The formation of Calligrammes

The various poems collected in Calligrammes were written between the end of 1912 and 1917 – in March of that year, Apollinaire began to organise the collection in a precise order. The section ‘Ondes’, written before the declaration of the war, opens the collection, followed by ‘Étendards’, written before the poet volunteered to go to the front in April 1915. ‘Case d’Armons’, which evokes the suffering of World War I, is succeeded by ‘Lueurs des tirs’, which focuses on love and life in the trenches. The latter sections ‘Obus couleur de lune’ and ‘La Tête étoilée’ combine notions of memory, daily life and the poetic vocation of the author. In August, he finished correcting his second set of proofs. The collection was published the following year by Mercure de France on 15 April 1918. Some poems had previously appeared in magazines such as Les Soirées de Paris and SIC.

Dedicated to a childhood friend who had died in battle, René Dalize, this collection is the last published in Apollinaire’s lifetime. In it, he appears as one of the first – and possibly one of the only! – champions of poetic daring of the 20th century. Calligrammes is in effect an exercise in surprising the reader, in demonstrating that poetry is hidden everywhere – almost in the form of poem-conversations – for those who make an effort to look beyond propriety and appearances. He offers a definition of ‘calligram’ in a letter to his friend André Billy, who had criticised the collection:

The Calligrammes are an idealisation of free verse poetry and typographical precision in an era when typography is reaching a brilliant end to its career, at the dawn of the new means of reproduction that are the cinema and the phonograph. If I stop these types of research one day, it will be because I’m tired of being treated as an oddball precisely because such research seems absurd to those who are happy to stick to the path of convention.

Indeed, since his early youth, Guillaume Apollinaire had worked as much at the form of his poetry as the content, and Calligrammes is the culmination of this process. Whether it is his verses that still resonate today…

Ah Dieu ! que la guerre est jolie

Avec ses chants ses longs loisirs

Cette bague je l’ai polie

Le vent se mêle à vos soupirs

… or his instantly recognisable figurative poems – ‘La Colombe poignardée et le Jet d’eau’ and ‘La Tour Eiffel’ – Apollinaire is as timeless as he is enduring. Part of the appeal of Calligrammes, poems more of war than of peace, is the quest for beauty in a universe of turmoil, where the violence of war is superimposed on the faces of loved ones.

A splendid document

There are several dossiers of handwritten and typed drafts that paint a picture of the varying and numerous stages of Apollinaire’s work on Calligrammes. This edition proposes to reproduce the maquette used for the Mercure de France edition of 1918. It contains 32 autograph manuscript pages and 154 pages of texts made of extracts from previous publications mounted on blank sheets with annotations, sketches and corrections. Each page turned brings the discovery of a new treasure.

The manuscript opens with the author's bibliography, followed by the colophon and title page, which includes the six main sections of the collection previously described. There are poignant drawings for the reader to discover: a Virgin and Child outlined in blue pencil to accompany the poem ‘Liens’; a sketch of Christ face-to-face with a soldier alongside ‘Le Musicien de Saint-Merry’ and many more. Flora and fauna, musical notation, ships and everyday objects, scatterings of typeface characters, gentle and furious crossings-out… the maquette is an invitation to travel into the imagination of a damaged but brilliant poet.

A great poet

At the start of 1918, Guillaume Apollinaire was unaware that his life would soon draw to a close. He had excelled in the artistic scene throughout 1917, with the first performance of Mamelles de Tirésias at the Conservatoire Renée Maubel in Montmartre in June, and his lecture ‘L’Esprit nouveau et les poètes’ at the Vieux-Colombier theatre in November. In January he was taken ill with congestion of the lungs, shortly afterwards contracting the Spanish flu which worsened the after-effects of his war injuries. He died on 9 November at the pinnacle of his artistic career, before reaching his fortieth birthday.

The Jacques Doucet Library (Paris)

The Jacques Doucet Library is dedicated to French literature from the second half of the 19th century to the present day. Created by the great couturier and patron of the Arts Jacques Doucet, it was bequeathed to the University of Paris in 1929. Since 1972 it has been under the responsibility of the Chancellerie des Universités de Paris.

A collector and patron of the Arts, the couturier Jacques Doucet (1853-1929) began building up an exceptional literary library in 1916, bringing together rare editions and documents (manuscripts, corrected proofs, correspondence, etc.). In 1933, thanks to Rector Charléty, the library was transferred and opened to the public at the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, place du Panthéon (Paris). The Jacques Doucet Library is enriched by prestigious donations and acquisitions. In addition to Jacques Doucet's personal collection, the general collection comprises 90 writers' fonds (Mallarmé, Verlaine, Apollinaire, Éluard...) as well as other artists archives (Derain, Picabia, Matisse, Nicolas de Staël...).

The collection comprises approximately 140,000 manuscripts, 50,000 enriched printed books, 800 literary and poetic reviews, over a thousand art bindings, plus photographs, paintings, drawings, prints and furnishings.

Bibliography:

- Calligrammes de Guillaume Apollinaire. Gallimard (Paris, 1948).

- Apollinaire : Œuvres poétiques complètes. Édition commentée par Marcel Adéma et Michel Décaudin, préface d’André Billy. Gallimard / Pléiade (Paris, 1956).

- Calligrammes de Guillaume Apollinaire (essai et dossier). Édition commentée par Claude Debon. Folio Poche (Paris, 2004). Et Calligrammes dans tous ses états, édition critique du recueil de Guillaume Apollinaire de Claude Debon, Calliopées (2008).

- Website of the Jacques Doucet Library

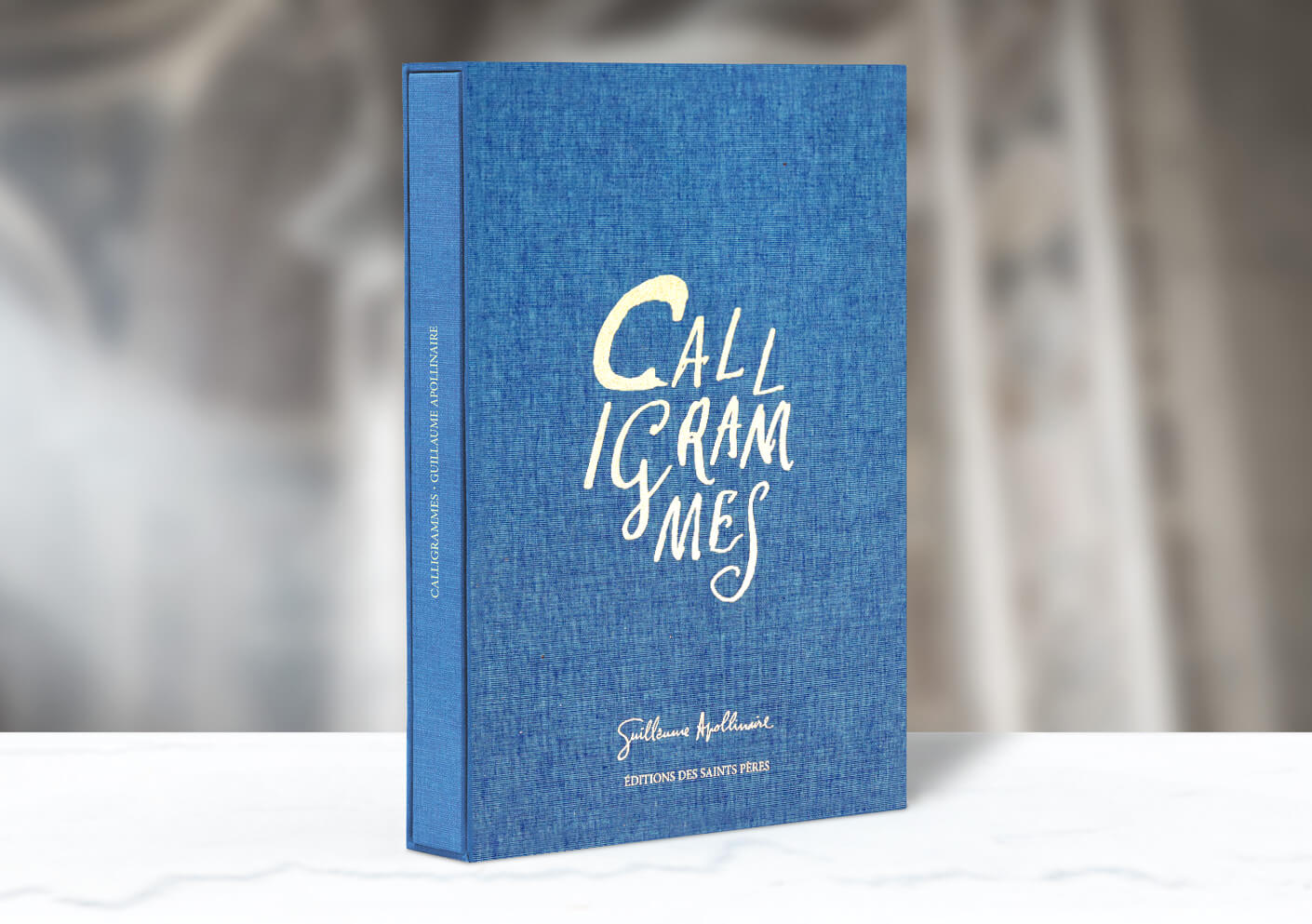

Deluxe edition

Numbered from 1 to 1,000, this Petrol blue edition is presented in a large format handmade slipcase.

Printed with vegetable-based ink on eco-friendly paper, each book is bound and sewn using only the finest materials.

Mrs Dalloway: Thanks to a new reproduction of the only full draft of Mrs. Dalloway, handwritten in three notebooks and initially titled “The Hours,” we now know that the story she completed — about a day in the life of a London housewife planning a dinner party — was a far cry from the one she’d set out to write (...)

The Grapes of Wrath: The handwritten manuscript of John Steinbeck’s masterpiece The Grapes of Wrath, complete with the swearwords excised from the published novel and revealing the urgency with which the author wrote, is to be published for the first time. There are scarcely any crossings-out or rewrites in the manuscript, although the original shows how publisher Viking Press edited out Steinbeck’s dozen uses of the word “fuck”, in an attempt to make the novel less controversial. (...)

Jane Eyre: This is a book for passionate people who are willing to discover Jane Eyre and Charlotte Brontë's work in a new way. Brontë's prose is clear, with only occasional modifications. She sometimes strikes out words, proposes others, circles a sentence she doesn't like and replaces it with another carefully crafted option. (...)

The Jungle Book: Some 173 sheets bearing Kipling’s elegant handwriting, and about a dozen drawings in black ink, offer insights into his creative process. The drawings were not published because they are unfinished, essentially works in progress. (...)

The Lost World: SP Books has published a new edition of The Lost World, Conan Doyle’s 1912 landmark adventure story. It reproduces Conan Doyle’s original manuscript for the first time, and includes a foreword by Jon Lellenberg: "It was very exciting to see, page by page, the creation of Conan Doyle’s story. To see the mind of the man as he wrote it". Among Conan Doyle’s archive, Lellenberg made an extraordinary discovery – a stash of photographs of the writer and his friends dressed as characters from the novel, with Conan Doyle taking the part of its combustible hero, Professor Challenger. (...)

Frankenstein: There is understandably a burst of activity surrounding the book’s 200th anniversary. The original, 1818 edition has been reissued, as paperback by Penguin Classics. There’s a beautifully illustrated hardcover, “The New Annotated Frankenstein” (Liveright) and a spectacular limited edition luxury facsimile by SP Books of the original manuscript in Shelley's own handwriting based on her notebooks. (...)

The Great Gatsby: But what if you require a big sumptuous volume to place under the tree? You won’t find anything more breathtaking than SP Books ’s facsimile of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s handwritten manuscript of The Great Gatsby, showing the deletions, emendations and reworked passages that eventually produced an American masterpiece (...)

Oliver Twist: In the first ever facsimile edition of the manuscript SP Books celebrates this iconic tale, revealing largely unseen edits that shed new light on the narrative of the story and on Dickens’s personality. Heavy lines blocking out text are intermixed with painterly arabesque annotations, while some characters' names are changed, including Oliver’s aunt Rose who was originally called Emily. The manuscript also provides insight into how Dickens censored his text, evident in the repeated attempts to curb his tendency towards over-emphasis and the use of violent language, particularly in moderating Bill Sikes’s brutality to Nancy. (...)

Peter Pan: It is the manuscript of the latter, one of the jewels of the Berg Collection in the New York Public Library, which is reproduced here for the first time. Peter’s adventures in Neverland, described in Barrie’s small neat handwriting, are brought to life by the evocative color plates with which the artist Gwynedd Hudson decorated one of the last editions to be published in Barrie’s lifetime. (...)