William Blake's Notebook by William Blake

Gilded edition,

numbered from 1 to 1,000,

Large format (10x 14'')

William Blake's notebook : a treasure he kept all his life

This literary and artistic document gives a uniquely intimate insight into the Romantic poet and artist William Blake’s creative process. Born on the 28th November 1757, Blake worked primarily as an engraver, printmaker and illustrator in his lifetime, accepting artistic commissions as well as pursuing his own painting and poetry. Well-known for his illuminated manuscripts, which showcased his own watercolor illustrations alongside his poems, his best-known works include Songs of Innocence and Experience, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell and Jerusalem. While he did sell artwork to patrons and organise exhibitions to showcase his work, Blake was nonetheless largely unrecognised in his lifetime, perhaps owing to his anti-establishment and unconventional views. His contribution to poetry and visual art is now universally acknowledged and Blake is heralded as one of the most influential and significant writers in English Literature.

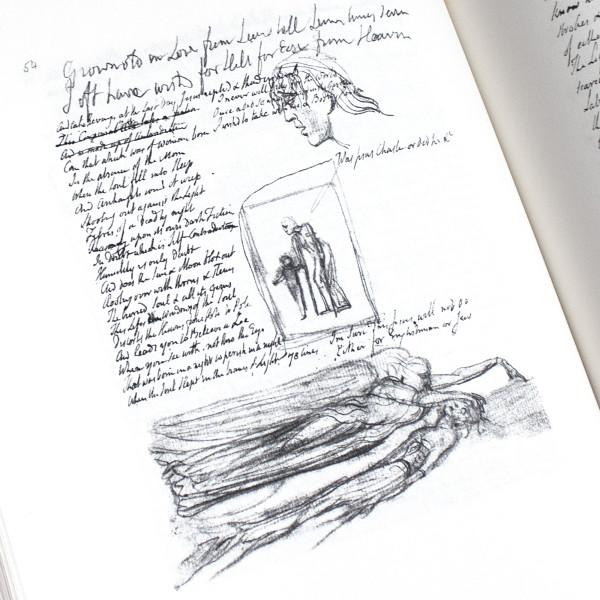

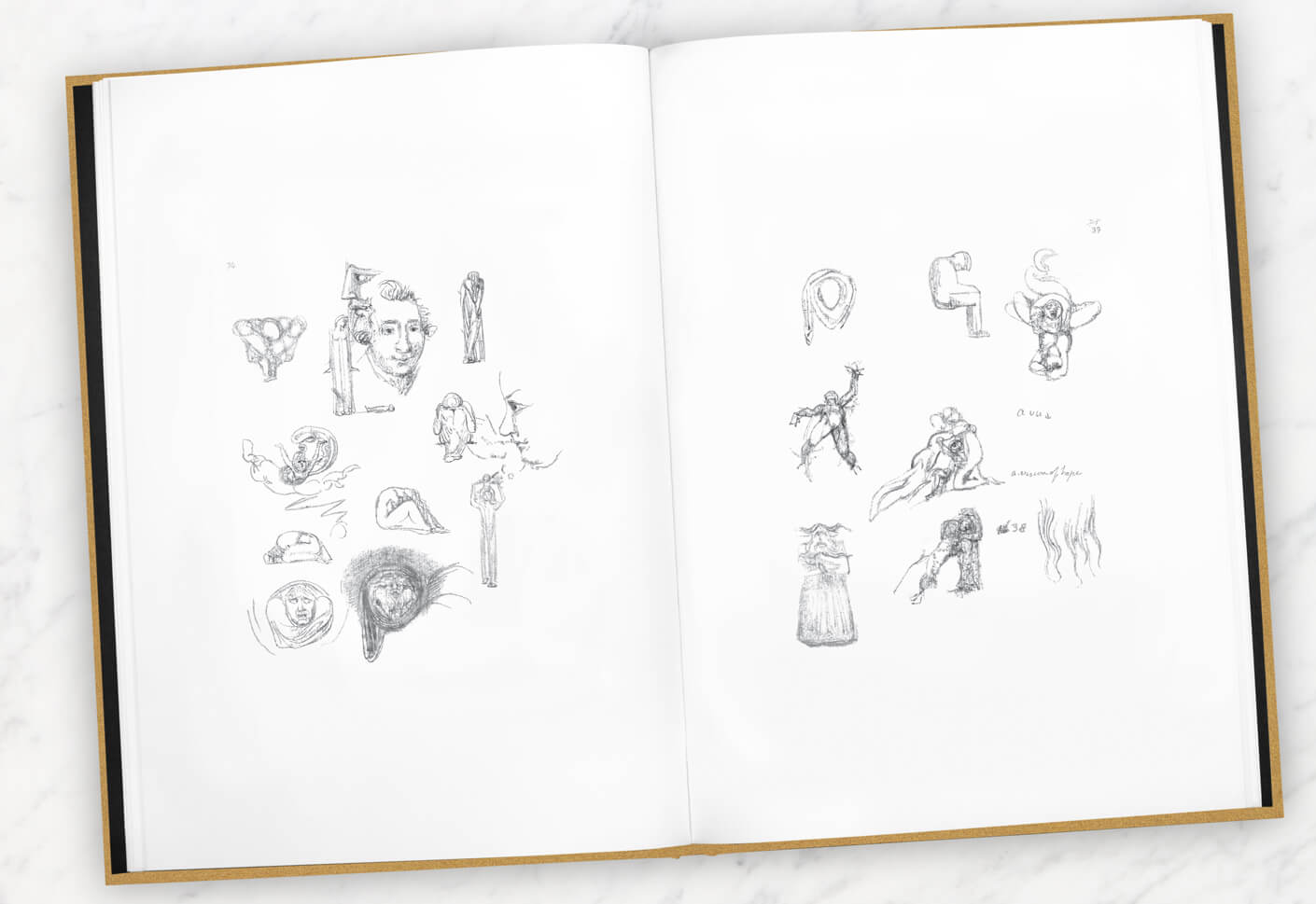

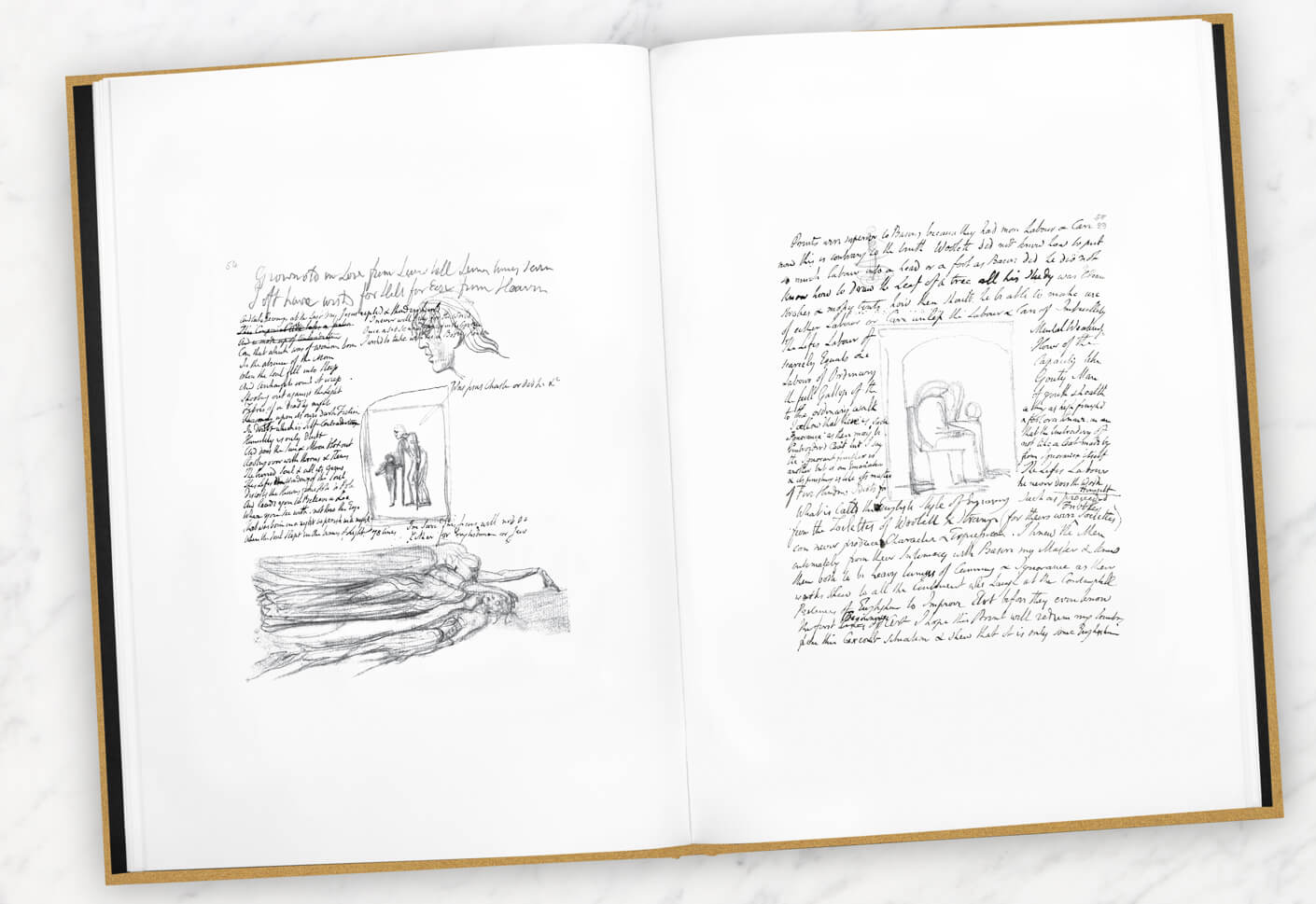

The notebook, which consists of 116 pages and measures 19.7 x 15.9 cm (7 3/4 x 6 1/4 in) was probably begun by William Blake’s younger brother Robert, whose sketches can be seen on several early pages of the notebook.

William Blake's imagination brought to life

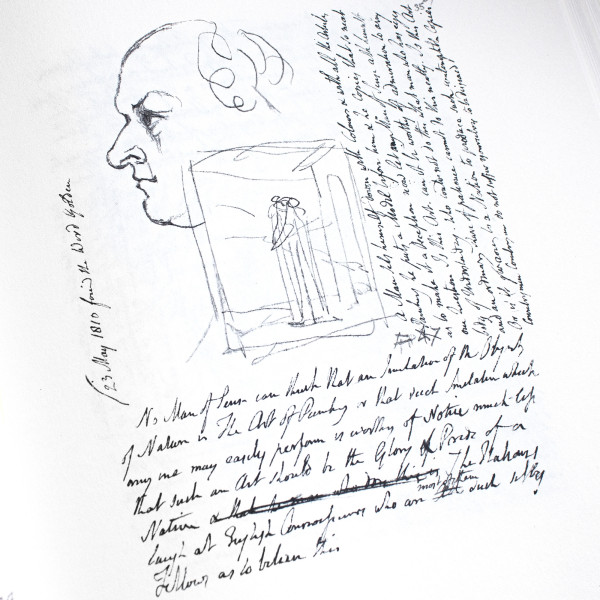

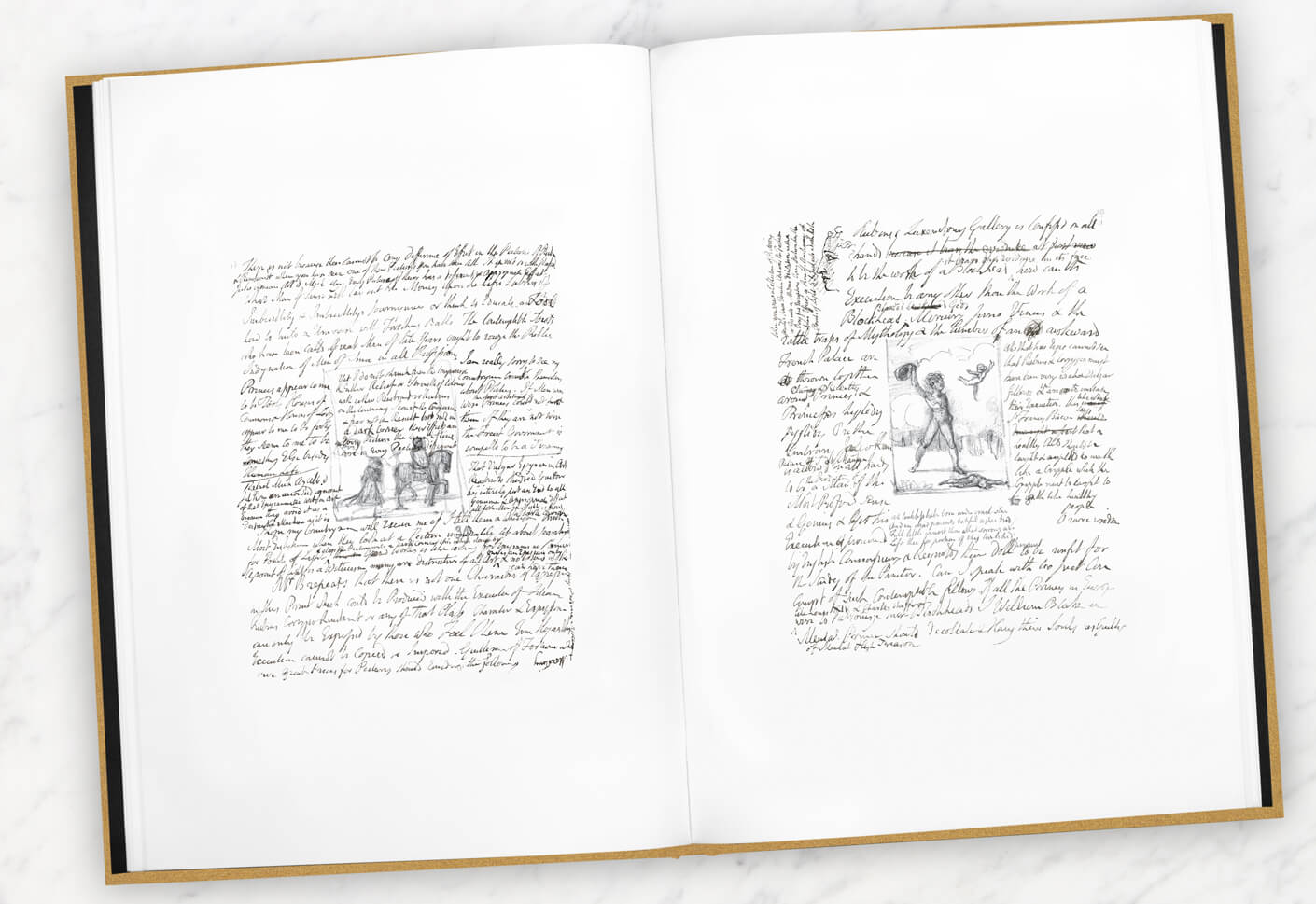

After Robert’s premature death in 1787, William inherited the notebook, keeping it beside him for more than three decades and adding sketches and writing intermittently, with his most intense period of usage between 1792 and 1794. Having covered every inch of available space on the right-hand pages, Blake promptly turned the notebook over and began working on the blank versos. His reluctance to part ways with this little book perhaps serves as evidence for its deep significance to him, both creatively and emotionally. Indeed, the loss of Robert marked him profoundly, a sentiment movingly expressed in a letter to his friend William Hayley written in 1800, ‘Thirteen years ago I lost a brother, and with his spirit I converse daily and hourly in the spirit, and see him in my remembrance, in the regions of my imagination.’

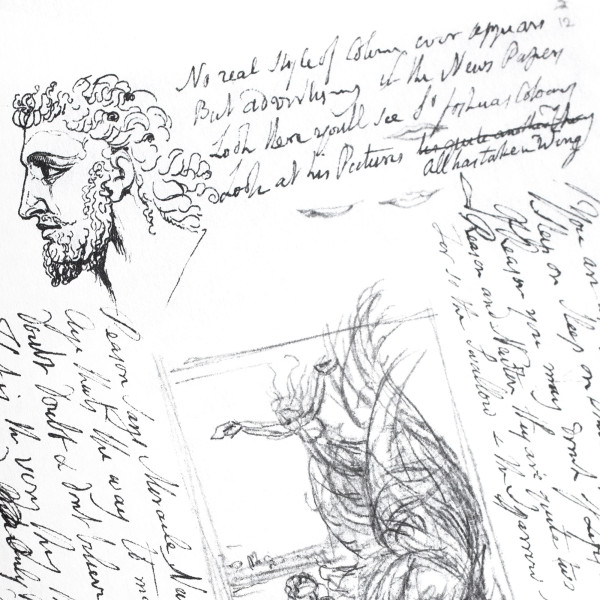

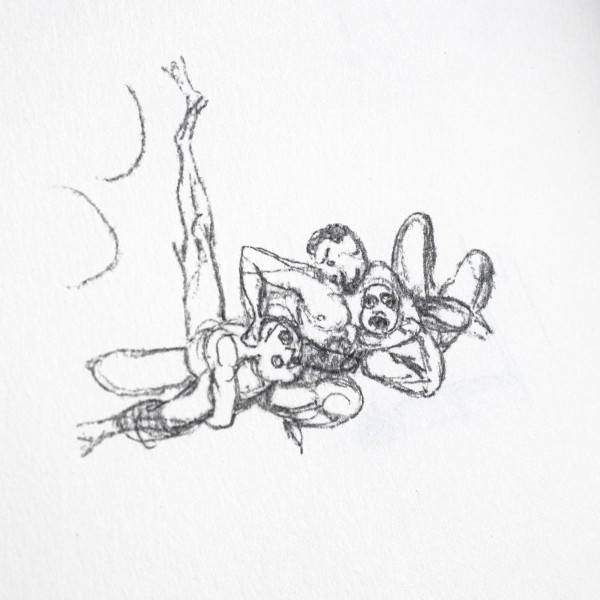

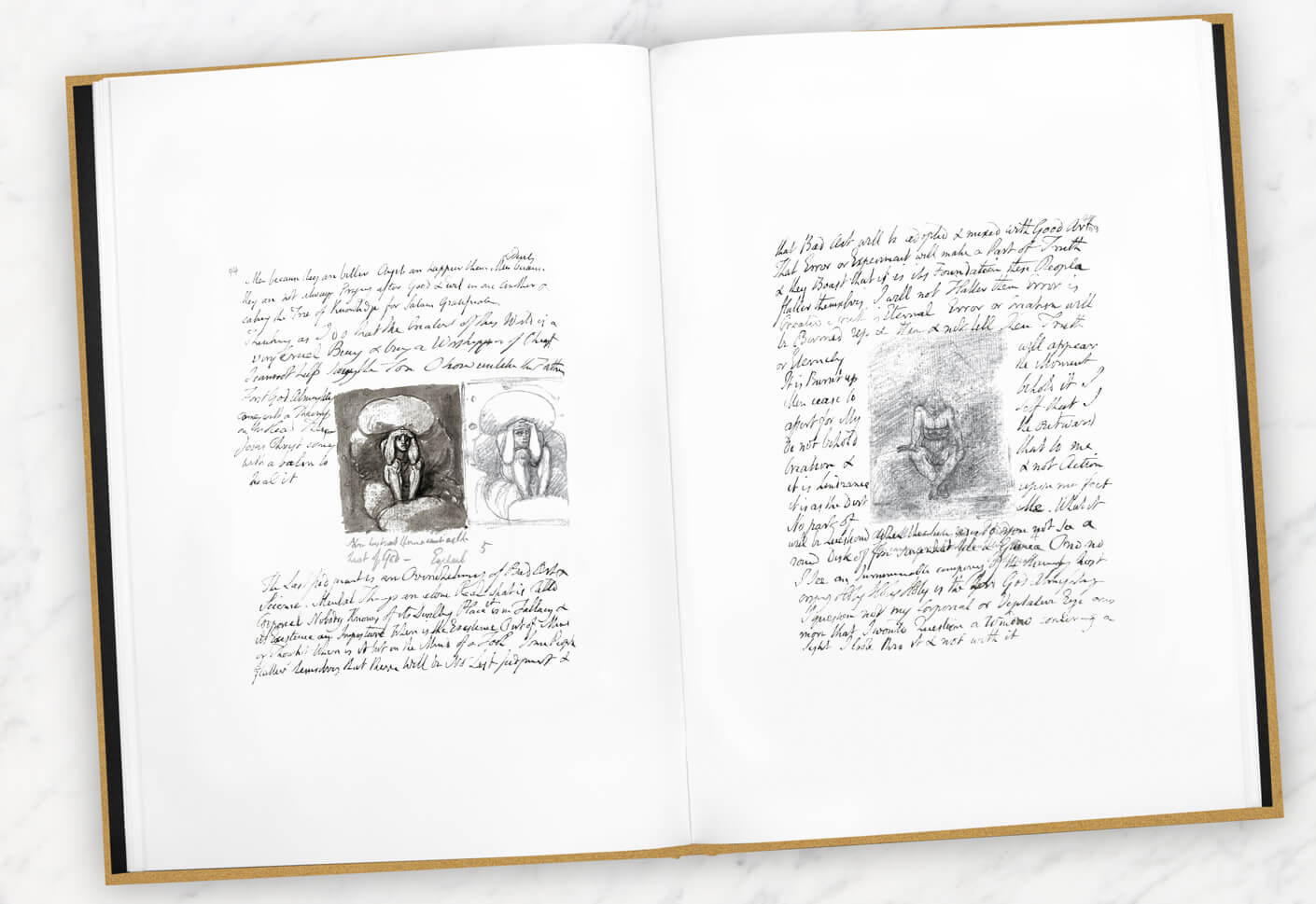

The notebook’s contents cover the span of Blake’s creative output; poetry and drawings abound, as well as quotations from Milton and Shakespeare and biographical references to specific moments in Blake’s career, such as his apprenticeship to the engraver James Basire, or his encounter with the prophetess Joanna Southcote, with whom he seems to have felt an affinity. On almost every page there are demons and curious beasts, and many faces, some imaginary, some clearly portraits: of Blake himself on p.67, of the revolutionary, Tom Paine, on p.74, and of a striking woman, probably his beloved wife Catherine, on p.82.

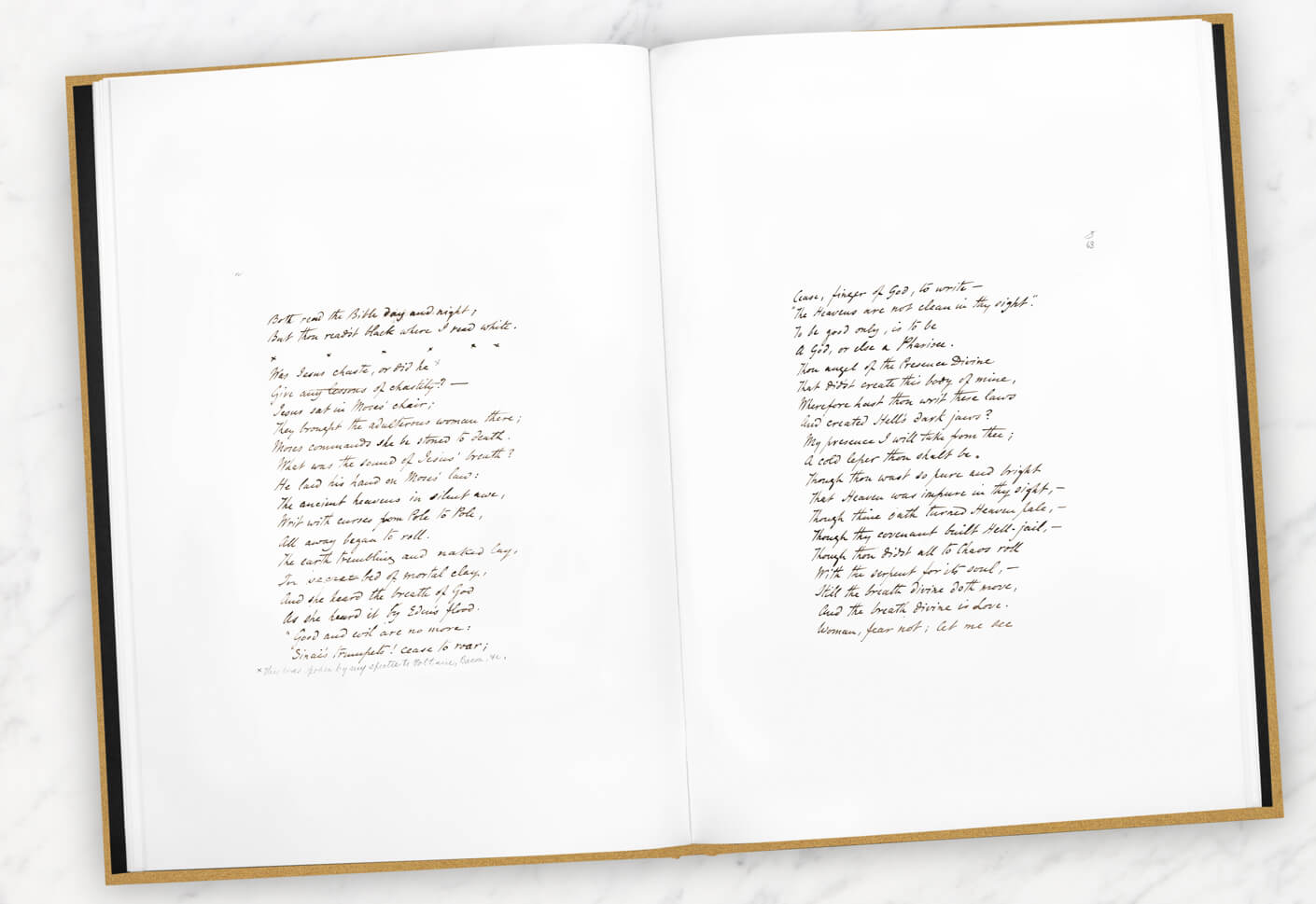

Contemplating the densely populated pages, it is possible to recognise the beginnings of some of Blake’s most emblematic works. Indeed, the notebook contains drafts for 16 of the poems that would later be included in Songs of Experience, including fragments from ‘London,’ ‘The Human Abstract’ and the first verse of ‘The Chimney Sweeper.’ Also present here are two draft versions of what is arguably Blake’s most famous poem ‘The Tyger,’ which merit comparison with the final version that would appear in his 1794 illuminated manuscript.

William Blake's intense creativity revealed

The notebook traverses many of the themes that would persist throughout Blake’s oeuvre, such as the tension between the human and divine, the hypocrisy of the Industrial Revolution and the subsequent destruction of nature and suffering of the working classes. The manuscript also offers the opportunity to engage with some of Blake’s more enigmatic work, such as ‘The Sick Rose,’ which has puzzled critics since its publication. Can deciphering Blake’s furious revisions and preliminary sketches for the poem offer a new interpretation?

Dante Gabriel Rossetti's fundamental role

Blake’s were not the only artistic hands through which this notebook passed. Indeed, its very existence today was assured by those into whose care it was placed after the poet died in 1827. Shortly after her husband’s death, Blake’s wife Catherine appears to have given the notebook to artist William Palmer in a gesture that ultimately assured the notebook’s existence today; Frederick Tatham, the inheritor of Blake’s estate after Catherine’s death, purportedly burnt a considerable portion of the poet’s work in a fit of religious fervour against its supposedly heretical content. Palmer, however, kept the notebook for over twenty years before selling it for ten shillings (about £40 in 2022) to a young artist destined for an extraordinary future - the nineteen-year-old Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who recorded his purchase in a penciled note on a blank page at the beginning of the notebook.

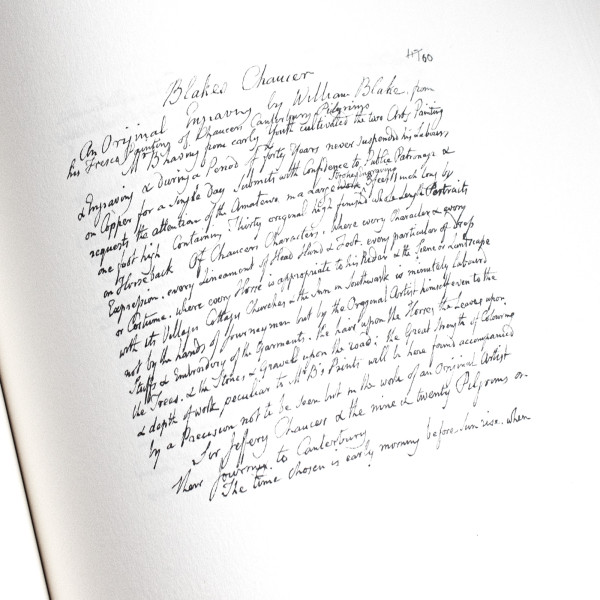

In 1850, and with the assistance of his brother, William Michael Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti transcribed and edited 42 of Blake’s poems from the notebook, which he eventually bound to the notebook itself as a 33-page appendix with the advisory note ‘All that is of any value in the foregoing pages has here been copied out. D.G. C. R.’

The Rossettis played an important role in popularizing Blake for a Victorian audience and allowed other artists and intellectuals the opportunity to see and draw inspiration from Blake’s work. Rossetti made the notebook available to the poet Algernon Swinburne and worked with Alexander Gilchrist in the 1850s to produce an early biography of Blake, entitled Life of William Blake, Pictor Ignotus.

It appears that Blake’s rebellious spirit was a source of inspiration for Rossetti and other members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, who, like Blake, rejected the more mechanistic style of the artists who directly followed Raphael’s example. Blake and the Pre-Raphaelites also found a common foe in the more contemporary English painter Sir Joshua Reynolds, who founded the Royal Academy of Arts and who favoured a more conventional approach to the process of making art.

However, the Rossetti brothers were also partially responsible for perpetuating misconceptions of Blake and his work that were more palatable to their own sensibilities. Dante Gabriel faced criticism from other Blake researchers, such as Richard Herne and John Sampson who felt that the Rossetti’s’ deviations from the original text misrepresented the reality of Blake’s complex life, work and ideology.

William Blake and Dante Gabriel Rossetti: a unique facsimile

Our reproduction of the manuscript is the first to include the pages added by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his brother, allowing the reader to make their own judgement.

Following Rossetti’s death in 1882 the notebook was sold at auction, where the bookseller, publisher and bibliographer Frederick Startridge Ellis became its new owner. After passing through various hands, it was acquired in 1887 by the bibliophile William Augustus White. In 1928 his daughter and heir Frances White Emerson donated it to the British Museum.

Deluxe edition

Numbered from 1 to 1,000, this Gilded edition is presented in a large format handmade slipcase.

Printed with vegetable-based ink on eco-friendly paper, each book is bound and sewn using only the finest materials.

Mrs Dalloway: Thanks to a new reproduction of the only full draft of Mrs. Dalloway, handwritten in three notebooks and initially titled “The Hours,” we now know that the story she completed — about a day in the life of a London housewife planning a dinner party — was a far cry from the one she’d set out to write (...)

The Grapes of Wrath: The handwritten manuscript of John Steinbeck’s masterpiece The Grapes of Wrath, complete with the swearwords excised from the published novel and revealing the urgency with which the author wrote, is to be published for the first time. There are scarcely any crossings-out or rewrites in the manuscript, although the original shows how publisher Viking Press edited out Steinbeck’s dozen uses of the word “fuck”, in an attempt to make the novel less controversial. (...)

Jane Eyre: This is a book for passionate people who are willing to discover Jane Eyre and Charlotte Brontë's work in a new way. Brontë's prose is clear, with only occasional modifications. She sometimes strikes out words, proposes others, circles a sentence she doesn't like and replaces it with another carefully crafted option. (...)

The Jungle Book: Some 173 sheets bearing Kipling’s elegant handwriting, and about a dozen drawings in black ink, offer insights into his creative process. The drawings were not published because they are unfinished, essentially works in progress. (...)

The Lost World: SP Books has published a new edition of The Lost World, Conan Doyle’s 1912 landmark adventure story. It reproduces Conan Doyle’s original manuscript for the first time, and includes a foreword by Jon Lellenberg: "It was very exciting to see, page by page, the creation of Conan Doyle’s story. To see the mind of the man as he wrote it". Among Conan Doyle’s archive, Lellenberg made an extraordinary discovery – a stash of photographs of the writer and his friends dressed as characters from the novel, with Conan Doyle taking the part of its combustible hero, Professor Challenger. (...)

Frankenstein: There is understandably a burst of activity surrounding the book’s 200th anniversary. The original, 1818 edition has been reissued, as paperback by Penguin Classics. There’s a beautifully illustrated hardcover, “The New Annotated Frankenstein” (Liveright) and a spectacular limited edition luxury facsimile by SP Books of the original manuscript in Shelley's own handwriting based on her notebooks. (...)

The Great Gatsby: But what if you require a big sumptuous volume to place under the tree? You won’t find anything more breathtaking than SP Books ’s facsimile of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s handwritten manuscript of The Great Gatsby, showing the deletions, emendations and reworked passages that eventually produced an American masterpiece (...)

Oliver Twist: In the first ever facsimile edition of the manuscript SP Books celebrates this iconic tale, revealing largely unseen edits that shed new light on the narrative of the story and on Dickens’s personality. Heavy lines blocking out text are intermixed with painterly arabesque annotations, while some characters' names are changed, including Oliver’s aunt Rose who was originally called Emily. The manuscript also provides insight into how Dickens censored his text, evident in the repeated attempts to curb his tendency towards over-emphasis and the use of violent language, particularly in moderating Bill Sikes’s brutality to Nancy. (...)

Peter Pan: It is the manuscript of the latter, one of the jewels of the Berg Collection in the New York Public Library, which is reproduced here for the first time. Peter’s adventures in Neverland, described in Barrie’s small neat handwriting, are brought to life by the evocative color plates with which the artist Gwynedd Hudson decorated one of the last editions to be published in Barrie’s lifetime. (...)